By Arjun Gupta, MD

By Arjun Gupta, MD

I met Dr. David H. Johnson for the first time in January 2014 at the internal medicine residency interview at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. At the end of the interview day, applicants, housestaff, and faculty members gathered for a reception (aptly termed liver rounds, to describe the beverages served). I was standing in a group of several applicants and residents, deep in conversation. Dr. Johnson, the chair of medicine, arrived wearing a crisp white coat. I later discovered his spotless white coat characterized most of his public appearances at the hospital. He stood by patiently until our group finished a conversation on the best tacos in Dallas—two residents had quite opposing thoughts and could not reach consensus. When they were done, he introduced himself, firmly shook our hands, and asked how our day went.

I wanted to tell him then that UT Southwestern was a dream residency program for me, in no small measure because I wanted to pursue oncology and learn from him. I was just in ninth grade learning about the cell cycle for the first time when he was already ASCO president! I had looked him up the evening before the interview, and a friend who was a resident in the program had told me how involved Dr. Johnson was in resident education and well-being. But I didn’t manage to find the words, and mingling meant I did not see him again that evening.

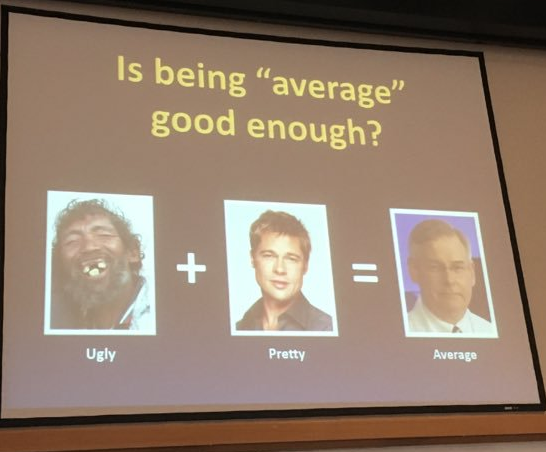

Fortunately, a few months later, I matched at UT Southwestern for residency. I was elated. I met Dr. Johnson again at residency orientation, where he gave an impassioned talk to us incoming interns. One of his slides in particular has stayed with me. First, he pointed that almost no one wants to be average—most people want to be above average. Yet, natural order demands someone to be average and even below average. Self-deprecating as always, he put up this photo of himself as average—the sum of a rather disheveled looking man and Brad Pitt. He implored us to be the best versions of ourselves, and not do anything half-heartedly.

Intern year started in gusto and soon it was my turn on the flagship rotation of our residency program, Parkland wards. Parkland Hospital (the Parkland of President Kennedy, and of the Burn Formula) has served as Dallas County’s safety net hospital for 120 years, and provides excellent care to some of the sickest patients in the country. When rotating on Parkland wards, interns take turns presenting a case to a senior faculty member on Tuesday afternoons. This was no small routine presentation. This was an event steeped in tradition: 20 eager interns, a whiteboard, and a master clinician. (To give you a sense of the esteemed faculty for these presentations, Dr. Donald Seldin, one of the most influential figures of modern American medicine, led this intern chart conference for over 50 years until a few months before his death in 2018.)

I looked at the presentation roster and saw that I was paired with Dr. Johnson. I prepared like a lunatic for the next 2 weeks, so much so that the chief resident refused to go over my teaching points again, and the patient asked me why I kept returning to examine her belly two or three times a day! The actual presentation went great. The patient was a previously healthy woman in her 40s presenting with a few weeks of fatigue and a petechial rash, who was eventually diagnosed with aplastic anemia. Dr. Johnson did ask early in the case presentation about splenomegaly—I was glad I had checked that, repeatedly! We had a lovely discussion about the utility (or rather, futility) of platelet transfusions prior to bone marrow biopsies even with severe thrombocytopenia.

I had hoped to speak to Dr. Johnson about a research idea after the conference, but he disappeared while I answered follow-up questions from co-interns. When I realized he was gone, I ran after him and found him just entering an elevator. It crossed my mind that I could join him in the notoriously snail-paced elevator and then he would be a captive audience to hear about my idea, but unfortunately the elevator was completely full. Instead, I sheepishly asked if I could speak to him. He smiled and stepped out, not betraying any hint of irritation at my stunt. (I would come to learn that he is incredibly gracious and patient. When a co-chief resident emailed him three times without attaching the intended document, he replied with a smiley and his characteristic ‘’Dr. J’’ signature.)

I fumbled and pushed up my badge for him to see my name, and told him my idea to explore the impact of obesity on outcomes for patients with lung cancer. He gave me an encouraging nod and said he would set up a meeting to chat more.

Overjoyed, I went back to the wards. A week passed and no email arrived. My enthusiasm started to nosedive. My imposter syndrome started to manifest. I thought to myself, “What did I ever do to deserve meeting him?! I should just focus on being an intern. I still know very little about renal tubular acidosis.’’ This self-pity proved needless when, a couple of days later, his assistant sent an email asking when I could meet Dr. Johnson. I almost jumped with joy.

Visiting his office was inspiring. It was exactly as I had anticipated—books, articles, journals, and paintings all over, and a crisp white coat, hanging neatly on a hook on the back of the door, ready for him to wear to his next engagement. It was actually too much to absorb during my first visit. In the years to come, I learned much just from visiting his office. I entered once to find him staring at a painting of The Doctor, and his impromptu reflections on the role of the physician prompted me to write about the Harry Potter series and its deep connection to medicine.

That first day, sitting across from Dr. Johnson, I presented my meta-analysis proposal. He pointed out that he himself had authored an article we could consider including in the meta-analysis. I do not know what it was—maybe I was euphoric, or maybe he made me feel that comfortable—but I blurted out, ‘’No, you did not measure premorbid BMI, so there is likely confounding by disease in that study.’’ He was stunned for a second, but quickly recovered and smiled, and agreed (I think) with the assessment. We worked on the project together and became closer. Publishing the paper and seeing my name as an author alongside his remains one of the proudest moments of my professional career.

Over the next couple of years, I frequently ran ideas by him at morning reports. I was amazed at how intently he listened, his punctuality (he would always be at morning report at 7:50 AM, ready for the scheduled 8 AM start), and his voracious appetite for reading—although we have somewhat different tastes. Despite always playing Gandalf to my Frodo, I am not sure he has read The Lord of the Rings—he has told me he has not read Harry Potter either, probably two of his only deficits. Meanwhile, an Oslerphile himself, he implores me even now to take some time to read about the history of Hopkins and Osler.

Residents often jokingly referred to morning report as ‘’story hour’’ because Dr. Johnson would mention engaging topics and the ensuing discussion would take a good part of the assigned hour: Theranos came up, and so did innovative care delivery models such as Outpatient Antibiotic Therapy (OPAT).

He also held monthly trivia sessions for the office staff. These were not easy! A sample question was estimating the volume of Big Tex’s hat (75 gallons, if you are interested). My performance in these quizzes was perhaps one arena where I persistently disappointed him. I also learned that he loves his Kentucky Derby Pie. His wide-ranging interests and his enthusiasm for sharing them are a major reason I became actively involved on Twitter. Five years later, I still keep an hour a week to read what he shares through social media—that hour is often not enough.

Dr. Johnson’s stories had a real impact on my work. He once shared in a private meeting how, in his 40s, when he was at the hospital actively receiving chemotherapy for lymphoma, he would sneak back into his office to work. That discussion and his personal and professional insights led me to undertake two quality improvement projects: reducing the delay for patients receiving chemotherapy, and transitioning multiday chemotherapy regimens to the outpatient space. Through his actions over years, minor and major, he directed me to a career in oncology quality and care delivery.

Deciding to stay on at UTSW for an extra year as chief resident was an easy decision—despite a limit on the number of years I could train in the U.S. while on a visa—because of the incredible personal mentorship from him afforded by the position. He told me, again in private, that quality and care delivery were the future, and I would do well to work on these topics in line with my passions. When I had an opportunity to work with Dr. Chris Moriates and Costs of Care but was nervous about taking the position due to bandwidth, Dr. Johnson advised me it was a cannot-miss opportunity, and sometimes we need to get out of our comfort zone.

His advice evolved over the years, and his manuscript edits changed from catching my every missing comma to big-picture comments: ‘’Did you consider this balancing measure?’’ or ‘’Did you read that paper from the Dartmouth Atlas published last week?’’

When the time to interview for oncology fellowship arrived, Dr. Johnson encouraged me to find the best fit with the best people. He introduced me to Simone’s Maxims, which have served me well in my short career. One of them—‘’Institutions don’t love you back… institutional relationships are really with persons, who can and sometimes do love you back.’’—is one I think about often. It is an uncomfortable thought, but reassuring in a way, that this job (like most things) is ultimately about the people. Ending up at Johns Hopkins for fellowship was no accident—it was the people and program leadership that attracted me here.

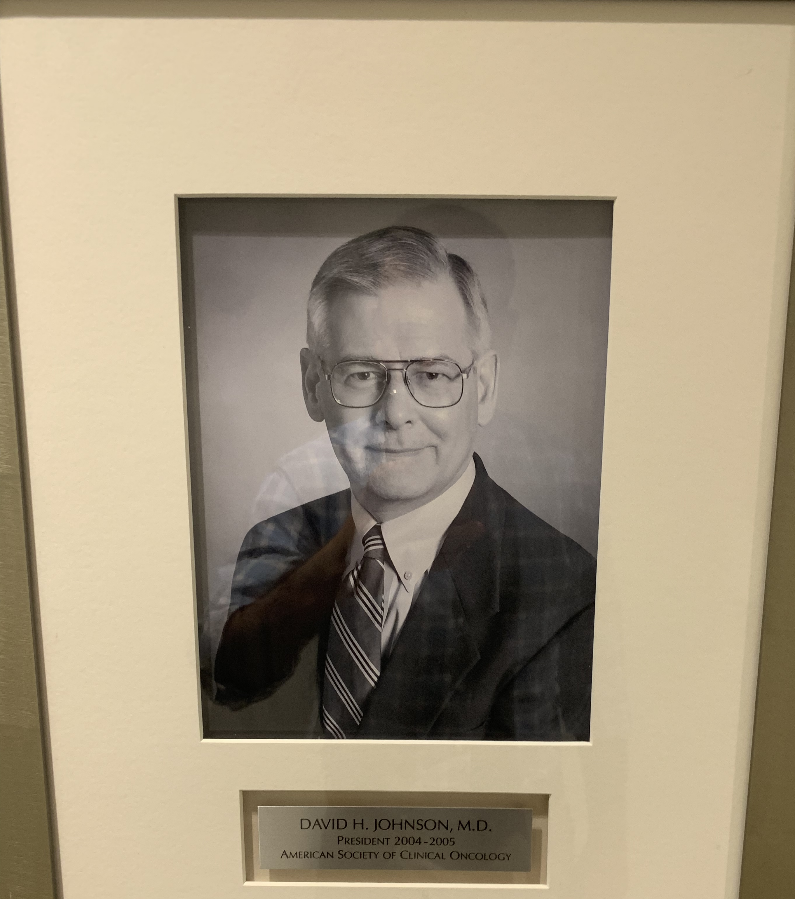

Dr. Johnson recommended very early in our relationship to keep a strong affiliation with ASCO. On a recent visit to ASCO headquarters in Alexandria, VA, I was walking the hallways and found this portrait of him from his time as president. I snapped this photograph meaning to send it to him, but never ended up doing so, figuring he would likely be embarrassed and shrug it off. (Of note, he reacted similarly when I shared this tribute with him prior to its publication, and spoke about symbiotic and gratifying mentor-mentee relationships and learning from each other.) I will just say that my 29-year-old self, reflected in the glass frame, is as much in awe of him now as my 14-year-old self would have been when he was ASCO president.

Earlier this year, Dr. Johnson announced his decision to step down as Chair of Medicine at UT Southwestern, after almost a decade in the role. Several of my friends at UT Southwestern texted me immediately about this announcement—which shows that my friends know me well, and know the admiration I have for Dr. Johnson. I sent him my regards the next day, with this picture of us at my residency graduation.

I also shared with him a clinical pearl he had taught us at a morning report, which I had applied in clinic just that week—‘’Question the diagnosis of small-cell lung cancer in a patient who has never smoked.'' That patient was eventually diagnosed with low-grade neuroendocrine tumor, with a quite different treatment paradigm. His reply was typically gracious, explaining his decision, asking me about my well-being, and hoping to meet at the ASCO Annual Meeting. Although I was there, I missed meeting him (McCormick Place is massive and a fellow’s salary does not support multi-day attendance).

I also missed his induction into the 2019 Giants of Cancer Care program a day before the official start of the ASCO meeting. I realize this was an invitation-only event, and I was not invited. But I felt a deep desire to attend and give him a standing ovation for minutes, as if doing so would communicate to him how much he has done for me, and no doubt, countless other mentees. Since I missed that event, I decided to pen this tribute to him.

Dr. Johnson, you are the best chair, teacher, mentor, and guide I could hope to have. I am very fortunate to be learning from you. Thank you.

Dr. Gupta is a medical oncology fellow at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Baltimore. He completed his residency and chief residency in internal medicine at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, under the chairmanship of Dr. David H. Johnson (@dhjutsw1). Follow Dr. Gupta on Twitter @guptaarjun90.

Recent posts