By Mona Hassan, MD

August 4, 2020, at 6:07 PM: what a moment, and what a huge impact it has made on the lives of everyone who was present in and outside Lebanon.

It was a regular working day. I am a PGY3 internal medicine resident rotating at the hematology and bone marrow transplant (BMT) unit of the American University of Beirut Medical Center (AUBMC). We finished our afternoon round and I headed to the library to get some work done. At the time in the evening, the hospital library, as usual, was filled with students and doctors.

At 6:07 PM, we heard a loud noise and the entire building shook. We all ducked under the tables in fear, thinking it was an earthquake; in fact, it was the first explosion of thousands of tons of ammonium nitrate that had been improperly stored at the Port of Beirut, although we did not know this yet. A few seconds later, the second explosion hit. All of the glass shattered and flew on us, and parts of the ceilings dropped. We were asked by the librarian to enter a room behind the library to hide, thinking that the explosion was there at AUBMC. These were minutes of fear, anticipation, and unknown—I cannot describe how long they passed, all the alarms were on and all the glass was on the floor. We then were asked to evacuate the building and go home, because at that time everyone thought the explosion was at AUBMC.

We all spent the next 10 minutes trying to call our families and our friends to tell them that we were okay and to make sure that they are okay! No one knew what happened and there was a lot of speculation of different sites for the explosion.

We went outside to find shattered glass everywhere; our hospital had no windows left! People were running like mad towards the ER. Security was yelling to evacuate the building because of the damage to the ceilings. Moments later, all residents received a WhatsApp message from our chiefs: “Guys a huge explosion happened Code D is activated please all doctors report to their respective department please do not all head to the ER.”

We met in the lobby. Each internal resident was sent to a floor to check on the patients, who had also been shattered with broken glass, and to try to discharge as many patients as we could, because we were expecting a huge wave of casualties. Everyone else was assigned to the ER.

As the hematology oncology floor resident, that was where I was assigned. On my way, I passed by the ER. It was like a scene from a horror movie—and yet, it was also a very amazing example of unity. All attendings, medical students, interns, and residents came from their homes to help. Even the heads of our pathology and radiology departments were on the front line to help care for the endless number of patients coming to the ER. I stood outside the ER for a second, trying to comprehend the situation, but I just couldn’t.

I went up to the hematology oncology floor. All my patients had shattered glass on them. I started to examine them one by one and make sure they were okay. Fortunately, most of them only had abrasions; only one person needed stitches. I helped get them out of the rooms while we cleaned the glass; everyone—medical students, interns, housekeeping staff, nurse managers—was helping to clean the patients’ rooms.

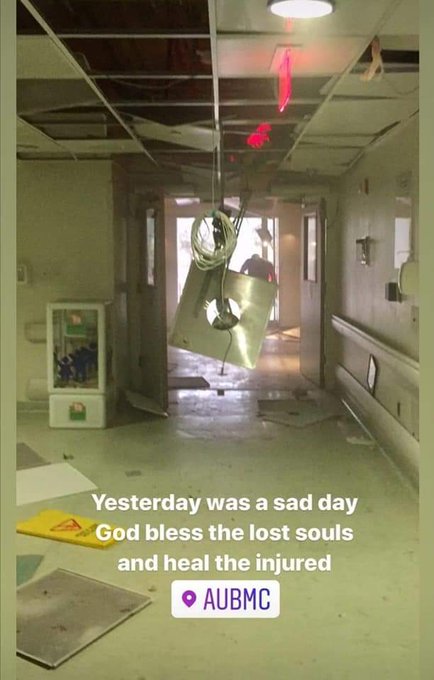

Images of the damage at AUBMC following the explosions.

My BMT attending had been in a patient’s room at the time of the explosion. I found him covered in blood, with injuries to his heel, his head, and his elbow. Thankfully only the heel injury was major. When I tried to remove the glass from it, I realized that he must have an arterial injury, because the blood would not stop. He refused to go to the ER, though, because he said there would be more injured patients, so I just cleaned it, did compression, and wrapped it. (The next day he was able to seek medical attention and have the wound stitched.)

Now I needed to discharge as many patients as I safely could. I did a round of all 45 patients, both oncology and hematology, and tried to see who was dischargeable. I started calling their corresponding attendings, and although a lot of the patients were cleared by the attending for discharge, they were so afraid to go home.

One of my patients, a woman with acute myeloid leukemia who has had two BMTs and was treated for central nervous system toxoplasmosis, told me, “Mona, I am so scared. I have never felt that death was so near like I did today.” She was absolutely crying and I was just standing there wishing I could hug her, but I could not, because we are still concerned with preventing the spread of COVID-19. At that point I had seen a lot of injured patients while wearing only a face mask, so I just couldn’t risk hugging her, for her own safety.

In the end, I discharged only 3 patients out of 45, because so few felt comfortable enough to go home during that night—they felt safer in the hospital. We did not force anyone to be discharged. We had cleaned up most of the glass in the patient rooms, and now injured patients from the ER started to come up to our floor. Most of the patients were unidentified, and since they had no charts on Epic, we started to write most orders on paper.

I had two medical students and an intern with me. We performed an ABCDE survey on every patient coming to our floor from the ER. We wrote down what surgical subspecialties each patient needed, and we started calling the ortho for open fractures, ophthalmo for injured eyes, plastic for face lacerations, etc.

My patients with cancer who were still on the floor were all crying, afraid for the people being admitted and how they were covered in blood. To keep everyone calm, I suggested to the nurse manager that we change the room distribution to put injured patients together and put our already admitted patients together, and that’s what we did. Family members of my patients with cancer went to donate blood.

Injured patients were crying in pain and in fear, wanting their families, who we were not able to let them see, and finally they were shocked and astonished by everything that happened—and trust me, so were we. I had phone calls asking me whether patients had been admitted to my floor, crying fathers and mothers asking about any information on their loved ones, and at that point our answer was that we still had no information.

At 1:30 AM, my chief called me and said, “Mona, tomorrow you have a regular working day. Please sleep and we will send a cover resident to take care of the patients.”

I was afraid to go home, so I went to the BMT unit and asked if there was a place I can sleep, since all the on-call rooms were full. They put a small mattress on the floor and covered it with bed sheets. The nurse gave me a chocolate bar and told me, “Mona, try to sleep. You have a long day tomorrow.”

That night I don’t think any of us slept. We were so tired, yet could not comprehend what had happened.

At 3:00 AM, a WhatsApp message chimed on our group chat: “Is anyone able to sleep?” Everyone said no. We started talking together, which was comforting, and then I opened social media, which was truly the biggest mistake. In horror I read that St. George, Karantina, and Wardieh Hospitals were completely destroyed and four nurses had died. Our hospital, AUBMC, was damaged, but at least we still had walls and none of us died! I started thinking that all of the things that were stored at the port were now destroyed, including all the chemotherapy medications that are given by the Ministry of Public Health to patients with cancer, and all of the homes in the areas around the port were destroyed. I finally cried myself to sleep for an hour or so.

I woke up at 6:30 AM and did a pre-round on my patients. Trauma patients were assigned to their surgical teams. It was Wednesday, so we had our weekly BMT/malignant hem multidisciplinary meeting that we do for all BMT and hematology patients admitted with the infectious disease team and the corresponding consulting teams. The show must go on, even after a disaster. Once the multidisciplinary meeting was done, I continued working until 5:30 PM, and then I finally went home, still not understanding what happened.

Now, a few weeks later, we are still seeing casualties from the explosion and from the protests post-explosion. We are seeing the disabilities and the scars. One of the biggest side effects of the explosion is the COVID-19 surge, with Lebanon recording more than 500 cases a day. We transformed from a country that had only about 2,000 cases before the explosion to a country with more than 10,000 recorded cases in less than 2 weeks, which is considered a lot for a country with four of its major hospitals destroyed. Most of the Beirut hospitals are working at full capacity because of the explosion and have 0 ICU beds available. A lot of health care workers have been infected with COVID-19 after the explosion, because despite wearing PPE as much as we can, some materials are not attainable in a disaster setting.

A week after the explosions, staff gather outside of AUBMC in solidarity with the Beirut hospitals that were destroyed in the blast.

Today, if you ask me what is next, I really do not know. We are living day by day. I really do not dare to have plans anymore. If you ask me if I am okay, I say I am physically okay, and for that I am extremely thankful. I am as okay as a PGY3 internal medicine resident and aspiring oncologist can be while training in a country that is so beautiful yet so ruined by corruption, a country struggling with a socioeconomic crisis, the aftermath of one of the most powerful non-nuclear explosions in history, and a surging global pandemic.

My message to you: In difficult times we discover that we are stronger than we think. Keep us in your prayers and please help Lebanon in any way, shape, or form you can. It is a country that does not deserve what is happening.

Dr. Hassan is a postgraduate year 3 resident in the Department of Internal Medicine at the American University of Beirut Medical Center, Lebanon. She is interested in pursuing a fellowship in hematology/oncology. She is a strong advocate for refugee rights and education with an interest in public health, and she serves as chair of the humanism fund at her hospital. Follow her on Twitter @mona_hssn.

Comments

Doug H.M. Pyle, MBA

Aug, 21 2020 10:03 AM

Thank you Dr. Hassan for sharing this. Our thoughts are with you and your colleagues during this exceptionally difficult time.

Nagi S. El Saghir, MD, FASCO, FACP

Aug, 22 2020 5:21 AM

Thank you @ASCOConnection for your support and for publishing this great piece by our sharp dedicated senior resident Dr @mona_hssn who describes the horrors and resilience witnessed at @AUB_Lebanon medical center and all over #Lebanon. She did a superb job with her fellow residents and attending and staff and volunteers during this those extraordinary times of disaster with over 450 immediate injured patients treated in our own Emergency Room alone! Other hospitals did the same and some were destroyed as she mentioned. More than 200 deaths and 6000 injuries. Dealing with complication and damages puts lots of strain on us and international support is essential!