Jun 06, 2023

Excerpt From the 2023 ASCO Annual Meeting Opening Session Presentation

By 2022-2023 ASCO President Eric P. Winer, MD, FASCO

My presidential theme, “Partnering With Patients: The Cornerstone of Clinical Care and Research” builds on my oncology career of more than 30 years and resonates with many of the challenges in oncology today. The theme promotes the preeminence of the relationship between the patient and the oncology clinician, which should be neither hierarchical nor unidirectional.

Some oncologists harbor concerns that they don’t have the time to establish a partnership with each of their patients, and I understand their apprehension. But I believe we must form these partnerships if we want to provide the very best cancer care and encourage our patients to participate in clinical trials.

Address continues below video.

My own thoughts about partnerships are influenced by my clinical work and my experiences beginning in childhood as a patient. Make no mistake, I do not think that one needs to have a lived experience as a patient either to understand or pursue an effective partnership with those for whom you care, and I will touch on this later.

Like my mother’s father and two of his brothers, who died in childhood, I was born with a bleeding disorder, hemophilia, in the era before effective treatments were available. I spent much of my childhood at Boston Children’s Hospital in a revolving door of hospitalizations and prolonged clinic visits to address recurrent bleeding episodes. My mobility was often limited, and my elbows were forever either bleeding or recovering from a recent bleed.

Above: Dr. Winer in childhood, with a splinted elbow.

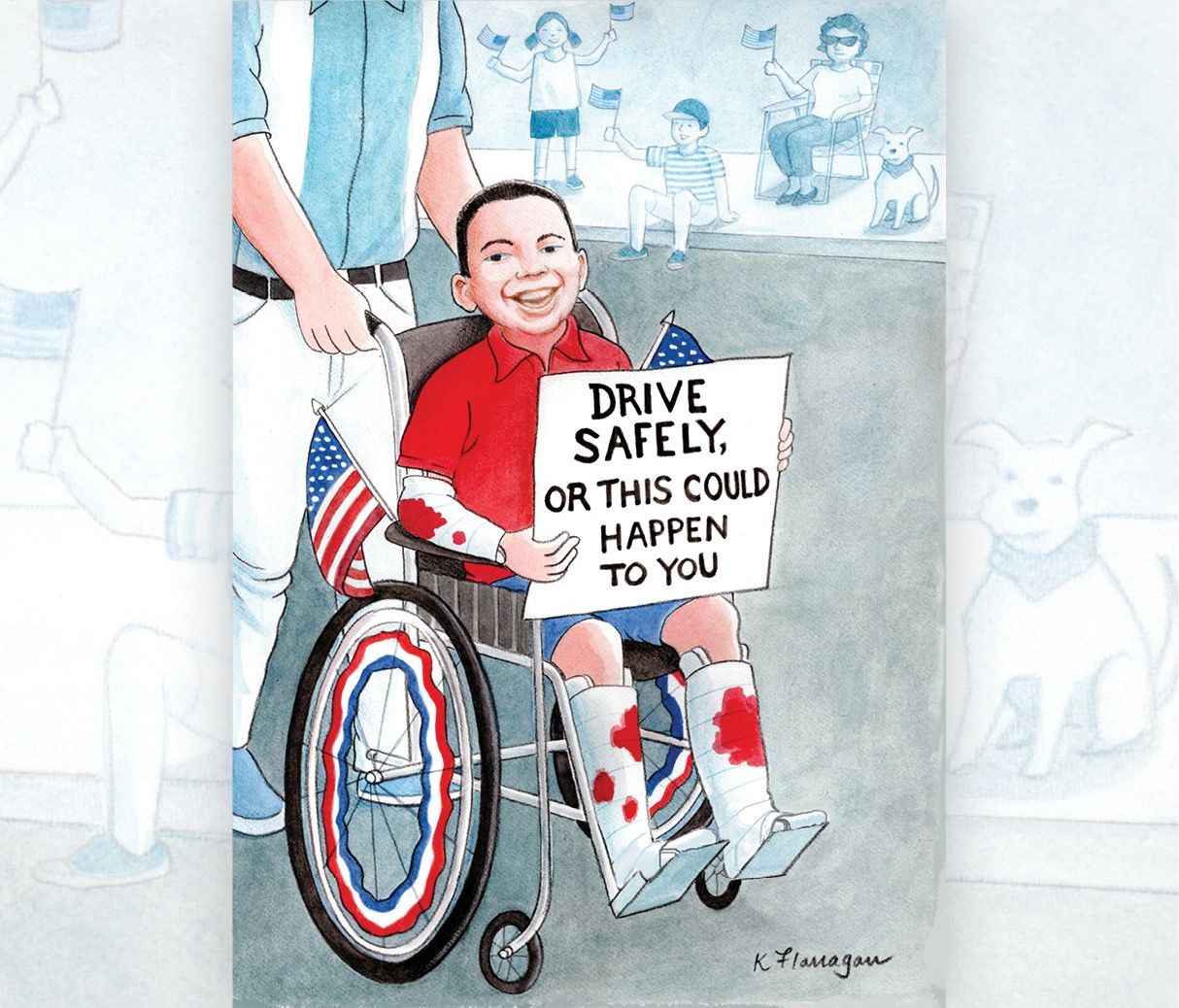

One July 4th, when I had splints on both ankles and an elbow, my parents—in an effort that showcased their determination and humor—made certain that I would not miss out on the town parade, pushing me along the streets in a wheelchair as I held a sign that said, “Drive safely, or this could happen to you.”

Above: An illustration of Dr. Winer at the July 4 parade as a child, drawn by his friend Kate Flanagan.

As I look back, I realize how much my parents sought out doctors who would partner with them and quickly moved on to a new physician if their voices were not heard. After all, they were experts in what I was going through. My father formed a lasting partnership with a forward-thinking orthopedic surgeon who taught him how to fashion splints to fit any joint, and that relationship not only kept me out of the hospital countless times, it provided all of us with tremendous confidence.

Above: Dr. Winer with his parents, Richard and Rhoda.

As I entered my teenage years, my life changed almost overnight. Factor VIII concentrates were developed, and I embarked on a routine of self-infusing clotting factor every other day. In most ways, I suddenly became a normal kid. I could find a vein and take factor anytime and anywhere, at home or school, on a trip, and even in the bathroom of a Greyhound bus.

I went off to college wanting to be a doctor but took a detour into Russian history. The son of the last Russian tsar also had hemophilia, and some thought that his illness was partially responsible for the downfall of the monarchy and the Russian revolution. Whether true or not, I immersed myself in all things Russian. I even had a tank of goldfish named after the last Russian imperial family.

But, when I finished college, I still felt compelled to be a doctor, and entered med school. In 1980, during my first year, one of my friends remarked about the progress in hemophilia treatment, suggesting any real health worries for me were a thing of the past. I agreed, but added that the impact of taking blood products derived from literally thousands of donors was unknown.

Little did I know that I had been infected with HIV the summer before, or of the devastating impact that was about to be unleashed in health care and the world at large.

Two years later, when the first three individuals with hemophilia were reported to have AIDS, I instinctively concluded that this mysterious illness was infectious and that virtually everyone with hemophilia was already infected. Initially, I was not particularly worried—the risks were uncertain, and I had many distractions. I finished medical school, slogged through internship like everyone else, and my wife, Nancy, and I were married the day after my internship.

Above: Dr. Winer and Dr. Nancy A. Borstelmann on their wedding day.

But as the statistics looked more alarming and as I took care of an increasing stream of patients with AIDS, the threat was hard to ignore. So, too, were the widespread misunderstandings about AIDS and the mounting social challenges.

In 1985, before I had even been tested for HIV—after all, there was no rush to be tested as I had no symptoms at that time and there was no treatment—I went to see my dentist for a much-needed root canal. As I was lying back in the dental chair, he entered and, with barely a greeting, asked me to leave the office. He claimed the staff had refused to treat me because of the risk they thought I posed.

I was abruptly denied access to care that I needed. I felt helpless, angry, and rapidly understood the power of stigmatization. I cannot tell you how relieved I was when I found a wonderful young dentist who took me into her practice.

I started to feel like I was living a life that needed to be played allegro… or even further up tempo. Nancy and I moved to North Carolina with our two sons under two, and by the end of my fellowship we had three great kids, all born in rapid succession.

Above: Dr. Winer's three children.

I, and by extension Nancy, were living a life on fast forward. By the early 90s, I had the foreboding sense that I might not live a long time. I had developed symptoms, and could not ignore the drenching night sweats, the mouth sores, the persistent rashes—and the mounting deaths. I was as frightened by what I might have to go through and put my family through as I was of dying.

Nancy and I were living with uncertainty and residing in a bubble of secrecy. Would our children be invited to play at the neighbor’s house if our neighbors knew that their father had HIV, and for that matter hepatitis C as well? I also doubted that my patients would want to see me if they knew about my health. I was leading a double life and guilt became my daily companion. So, too, was the fear that I might not be able to keep my job and what that would mean for our family and me personally, given my role and identity as an oncologist.

There is no need to detail the thousands of entries into my health records. For reasons I cannot explain, I have survived almost 45 years of HIV and was cured of hepatitis C after two long courses of interferon. As a result of portal hypertension from one of my first HIV medications, I had years of uncontrolled GI bleeding, quite a challenge for someone with a bleeding disorder. Ultimately, I found a transplant surgeon—a physician partner who listened to me and decided with me to proceed with a venous shunt. My GI bleeding stopped, and for the past 15 years I have been in better health than I was at age 30, 40, or 50.

The question is, what have I learned from this chronicle that could be helpful to all of you, and more specifically, how does my experience contribute to our collective understanding of partnerships between patients and clinicians in oncology?

Lesson 1: For the patient with serious illness, the relationship with the health care team is paramount.

When you are well, your relationship with the health care team, if you even have a health care provider, has almost no impact on your overall quality of life. In contrast, in the setting of serious illness those relationships are essential.

I have been privileged to have many great doctors who have added years to my life and have also helped me live an active and remarkably normal life. I have also had some pretty mediocre doctors, the ones who barely glance at you, or convey any sense that they care. Patients with cancer and their families need more from us and deserve the very best we can provide.

Lesson 2: Science really matters.

We owe it to our patients to step firmly on the scientific accelerator. The discoveries of the past several decades have been monumental in cancer medicine; basic, translational, clinical, and population-based research has led to life-altering progress and will ultimately allow us to eliminate death and suffering from cancer, assuming we can deliver the best care to everyone.

Now, more than ever before, we need to reach out to our own patients, the patient community at large, and the general public, to understand what we need to prioritize to make their lives better, and we need to listen to their guidance. We must embrace patients as our partners in research.

Lesson 3: If you scratch below the surface, everyone has a challenge in their lives—small, big, or bigger.

Precious few of us lead lives filled with never-ending sunshine and an absence of worries. We may have different struggles from one another, but we all face adversity and can learn and grow from it. We all have a lived experience that we can draw upon and is relevant to the work that we do as oncologists. Our own narratives can help us form better partnerships.

Lesson 4: People have very different reactions to what may seem to be similar challenges.

As physicians, we can’t expect patients to respond to hardships in a similar manner to us or to one another. Nor are patients required to be positive and cooperative all of the time.

I often tell patients that although they never would have asked for cancer diagnosis, they should try to extract something positive from it. Some can and others can’t, but in either case, we have to meet people where they are and support them.

They will make different decisions based on their own very legitimate preferences. A musician may choose to avoid neuropathy at almost any cost. A young parent may refuse to take any treatment that will compromise their ability to care for their children. And yet others may say they will pursue any therapy, no matter what happens, as long as it maximizes the chances of a cancer-free outcome.

It’s also important for us to remember and recognize that the newly diagnosed person we encounter at our initial meeting may evolve with and after cancer.

Finally, lesson 5: Stigma is devasting and we must take steps to protect our patients from it.

Illness is hard, but illness that leads to stigmatization is crushing. This was true of HIV for years, and my outrage would peak when people commented that I contracted HIV in a so-called socially acceptable manner.

Cancer was also a source of stigmatization for decades. While much of the stigma has dissipated, let me ask you: Should an individual with lung cancer who has been addicted to tobacco—and probably tried repeatedly to quit—be treated any differently from the non-smoker with lung cancer? Patients should receive our empathy, our humanity, and the best possible care, no matter how they find their way to our clinic.

As discussed in a National Academy of Medicine review on partnering with patients, the patient should be an integral part of the health care team, and decisions on care should be personalized and shared. The patient lives with their illness 24/7, and is the expert in how they feel on a moment-to-moment basis. When patients and their family members are fully involved in care decisions, the medical outcomes are better, readmission rates decline, adverse events are less frequent, and patients are more satisfied with their experience.

By building stronger partnerships, we can also help diminish cancer care disparities.

Two years ago, the [ASCO] presidential theme focused on equity in oncology care, a topic that becomes ever more important as our therapies become more complex and expensive. As we consider patient-clinician partnerships, it is imperative that we emphasize the challenges faced by the many individuals at risk for cancer care disparities, including patients who are from racial and ethnic minorities, patients living in poverty, patients from the LGBTQ+ community, those with mental health challenges, and so many others.

For these individuals, partnerships with physicians may be even more difficult to form, often because of structural barriers, but are absolutely indispensable if we are to mitigate inequities in cancer care. These are perhaps the most important partnerships of all.

I also believe that partnerships are crucial for the well-being and career fulfillment of oncologists.

I have long thought that most oncologists, as well as all of the members of the oncology care team, are a unique and special group of people. They are insightful, dedicated, and empathic. Most of us did not happen upon oncology—we actively opted for oncology as a mission-driven career and a lifestyle choice, not that this means that work needs to consume one’s entire life. But when an oncologist enters a room with a patient, there is an opportunity to open a door and walk into a patient’s life in a way that is true of very few other fields. There is no absolute requirement that you walk through that door, but if you do, the experience can be rich and rewarding.

Over the years, I have had countless relationships with patients and their loved ones that have filled with me satisfaction, pride, and sometimes sadness. And I know that many of you share this experience. In a recent ASCO well-being survey conducted in over 400 oncologists, almost two-thirds reported that talking to and advising patients provided joy.

I believe that strong clinician-patient partnerships strengthen us as clinicians and are an antidote for the much-discussed concept of burnout. The challenge is that health care systems, third-party payors, and leaders in oncology also need to value these critical partnerships and provide clinicians with the flexibility and freedom to establish them.

Unnecessary tasks abound in our work lives. The need to obtain prior authorizations, the regulations leading to excessive documentation in clinical care and clinical trials, and other similar activities deplete all of us. The incessant mouse clicks and the ever-mounting electronic signatures need to be reduced.

This year, ASCO’s board retreat focused on clinician well-being. As a powerful convenor, ASCO can advocate and help ensure that clinicians spend their time diagnosing, treating, and establishing relationships with patients. You will hear more in the future about these efforts but be confident that our Society is determined to have an impact on our capacity as clinicians to develop effective partnerships with our patients. In this way, we will ensure the best care for all individuals with cancer, the success of clinical trials, and the well-being of the workforce.

I have many, many to thank and too little time.

First of all, I am grateful for Lynn and Alexandra’s generosity in sharing their own experiences on the videos.*

Thanks to my friend Kate, for the drawing of me in the wheelchair on that distant July 4th.

I am grateful and truly humbled by the thousands of individuals with breast cancer who have shared their stories with me and allowed me to play a role, at times a pivotal one, in their care over the past three decades.

I am extraordinarily fortunate to have so many friends and collaborators in oncology. First, thank you to my incredible Dana-Farber breast cancer colleagues with whom I worked with for over 20 years. Leaving you was the most challenging part of my move to Yale. There are so many of you I could recognize individually, but I have to acknowledge Ann Partridge and Ian Krop, and I was delighted when Ian chose to join me at Yale.

My new Yale family has been welcoming, supportive, and—what can I say?—a gift. I have special thanks for my deputy directors Melinda Irwin, Roy Herbst, and Dan Dimaio, and our dean, Nancy Brown, for recruiting me to Yale and for her visionary leadership.

Then there is the ASCO crew. The ASCO staff are bright, dedicated, engaged, and always there when you need them. My close friend Cliff Hudis, ASCO CEO, has done a heroic job in his role and has achieved new and unprecedented heights for ASCO over the past 6 years. I learn from him every day. I want to call out my [Annual Meeting] Scientific Program and Education Committee chairs, Kimmie Ng and Shom Goel. I can’t imagine a better duo. Finally, it has been an incredible experience to serve with my fellow [ASCO] presidents: Lori Pierce, Everett Vokes, Lynn Schuchter, and Robin Zon. They keep me on my toes and are the very best colleagues.

Above: ASCO past, current, and incoming presidents. From left to right: Dr. Lori Pierce, Dr. Robin Zon, Dr. Lynn Schuchter, Dr. Winer, and Dr. Everett Vokes.

I would not be who I am were not for my parents, Richard and Rhoda Winer, who taught me at an early age that some people have blue eyes and some have brown, and some have hemophilia and others don’t. My mother died during the pandemic but had a very full life. My father, who turned 91 last month, exercises every day, drives effortlessly and (we hope) flawlessly, is sharp as a tack, and is here with his partner, Marilyn.

Above: Richard and Rhoda Winer.

Our thoughtful, generous, and accomplished children, Jeffrey, Joel, and Emily, have all gone into health care in different areas—clinical psychology, gynecology, and public health. They bring me endless pride and joy. I am so lucky to have been a dad, and, more importantly, to have had the privilege to see them become adults. Their spouses and partners, Meghan, Matt, and Jeremy, have expanded the family and are the perfect partners for our kids.

Above: Dr. Winer's children and their partners.

And then there are the two granddaughters, Lucy and Hazel, who are cute, charming, and of course brilliant. We look forward to each new chapter.

Above: Dr. Winer's granddaughters.

Finally, sitting in the front row with the whole family is Nancy Borstelmann, my wife of 39 years, who wins the family award for the most letters after her name from accumulated graduate degrees and focuses on mental health in oncology.

Our kids think I am fine, maybe a little distracted and sometimes demanding, but they view their mother as a saint, and I do too. She supported me through some very difficult times and was the only person with whom I truly shared my fears. The optimism that I displayed to the world often waned when I entered the door of our house. She has been there for me every step of the way even when she was dealing with the reality that she might become a single mother raising three children. Many marriages might not have survived, but ours has thrived because of Nancy’s compassion, judgment, strength, and love.

Nan, no words will ever do you justice.

Above: Dr. Borstelmann and Dr. Winer.

Being an oncologist has been an essential part of my life—it is hard for me to imagine any more rewarding career. I hope I have conveyed why I feel so deeply about the relationships we have with our patients, and what those relationships can mean to patients and to each of us.

*Editor’s note: Excerpt has been edited for length, style, and clarity. Lynn and Alexandra’s stories were highlighted in a video segment within Dr. Winer’s address, and can be viewed in the embedded video at the top of the page.