By Yara Abdou, MD

By Yara Abdou, MD

Peer review is not a task—it’s a privilege. It is a privilege to be able to contribute to the advancement of scientific research and to help maintain the credibility and integrity of research output. Peer review is not only essential for validating scholarly research, it’s also an invaluable experience for the reviewers themselves as they enhance their critical thinking skills and engage in an invigorating academic community.

Types of Peer Review

There are three major types of peer review; single blind, double blind and open. Single blind is the most common form of peer review amongst scientific journals. In this type, the authors do not know the identity of their reviewers. In double-blind review, the reviewers don’t know who the authors are and vice versa. In open peer review, the identity of the authors and the reviewers are known by both parties. In this type, the review may be published along with the accepted manuscript.

Invitation to Peer Review

Before accepting an invitation to review a paper, you must ensure that you have the expertise needed to provide an insightful and high-quality review. Additionally, you must agree to the time commitment required to complete this review and additional revised versions if needed.

Peer reviewers have a huge impact on the publication decisions made by the journal editors. Therefore, you have a responsibility to declare any conflicts of interest, be fair and objective with your feedback, and ensure that your comments are constructive and courteous, even when being critical.

Peer Review Structure

Most journals expect reviewers to provide authors with detailed feedback and comments, in addition to confidential remarks to the editor. Some journals, like the Journal of Clinical Oncology (for which I was an editorial fellow), have additional questionnaires in which they ask reviewers to score various attributes of the manuscript, including originality, scientific strength, quality of writing, relevance to clinical practice, and ethical standards. Finally, a publication recommendation is usually required. In most journals, there will be a list of choices to pick from: accept, minor revision, major revision, or reject.

Peer Review Process

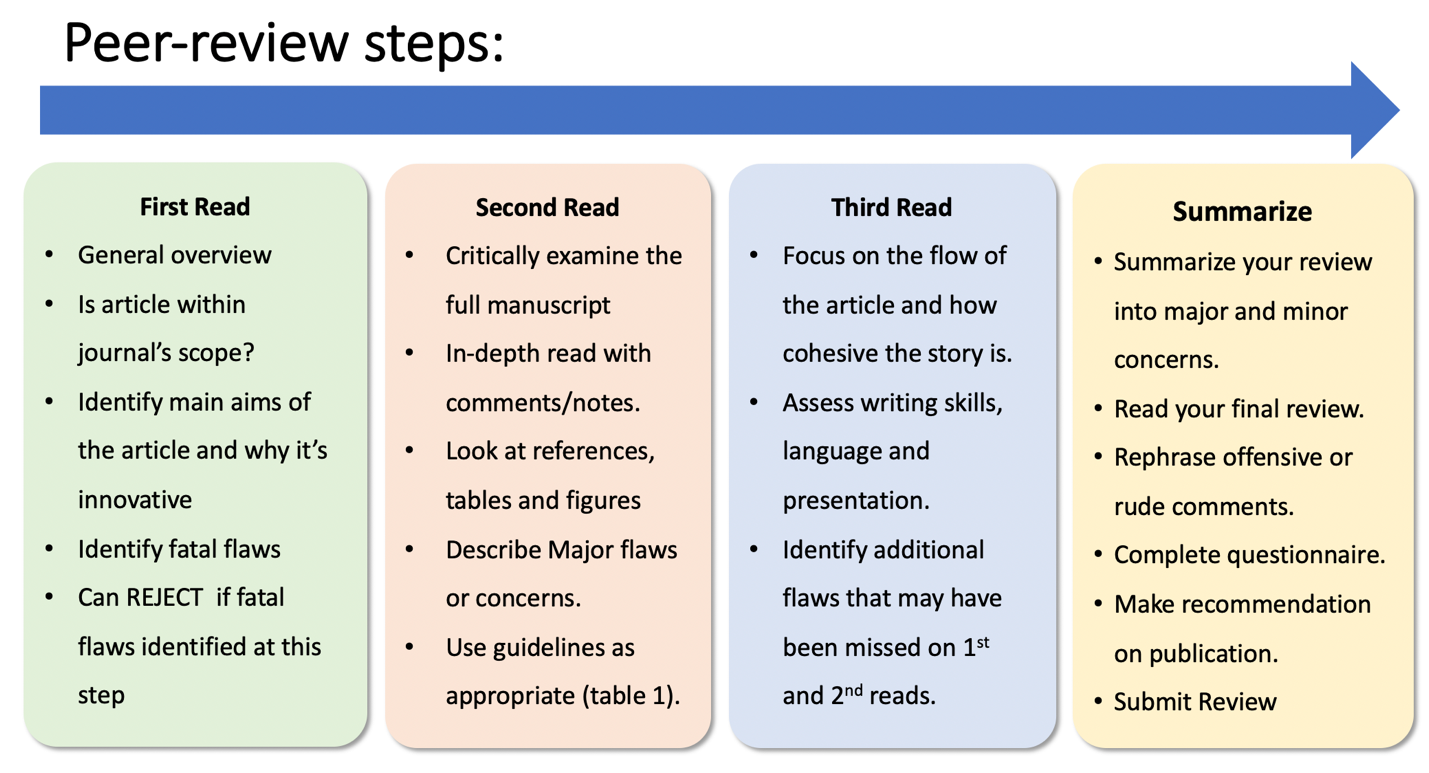

Once you receive the material, a first read-through is recommended for a general overview of the article. Here, you should focus on whether the article is within the scope of the journal, the innovativeness and originality of the study, and whether the aims and results are clearly iterated. Any fundamental flaws in the study design may be picked up at this point. If fatal flaws are detected, then the paper can be rejected after the first read.

If the manuscript does not have any immediate red flags, the next step is to give it a second, detailed read-though, making separate notes and comments. Published guidelines or checklists should be used as appropriate depending on the study type (see Table 1). Several aspects are taken into consideration during the second read:

- Does the title appropriately reflect the topic of the paper?

- Is the literature review up-to-date and does it place the study in an appropriate research context?

- Are the methods and analysis robust and clear?

- Are the results clearly and logically presented?

- Are there any ethical issues that were not addressed?

- Is the discussion insightful?

- Is there a balance between interpretation of the results and meaningful speculations?

- Are the limitations discussed in adequate detail?

- Are the tables and figures well-defined and helpful?

- Are the conclusions valid and adequately supported by the results?

- Are the references accurate, recent, and inclusive of similar published studies?

The third and last read should focus on the writing and the presentation of the manuscript. At this step, any gaps or inconsistencies in the story need to be addressed. Any areas with ambiguous meaning or factual errors should be identified. Once you complete the third read, you will have enough information to compile your notes into a single, comprehensive review report. Figure 1 below provides a summary of the steps involved in the review process.

Comments to the Author

There is usually no formally defined format for your comments to the manuscript’s author. Most commonly, reviewers begin their report with a paragraph summarizing the paper, followed by bullet points describing major and minor issues. The summary usually includes what the paper is about and what the main findings are. Strengths and weaknesses of the paper may be included in this section, in addition to the novelty and significance of the study.

The list of major issues indicates the significant revisions the paper needs in order to be published. This section usually discusses any major flaws and their impact on the paper; suggestions to improve on these flaws are encouraged. Any missing citations or discussions need to be mentioned here. Ethical concerns also need to be addressed in this section.

The list of minor issues can include any corrections indicated for factual errors, inaccurately phrased or ambiguous sentences, and mislabeled tables or figures.

Reviewers need to ensure that their comments to the author are clear and specific, while remaining objective and courteous. McPeek et al suggest a “golden rule” for peer review: you should review for others as you would have others review for you (American Naturalist. 2009;173:E155-8).

In providing comments to the author, do:

- Be specific and give examples from the manuscript. Suggest corrective actions when possible.

- Be objective. Distinguish factual comments from your own opinion.

- Prioritize your concerns. Only mention flaws if they matter.

- Be courteous and constructive.

Do not:

- Provide vague comments. It is frustrating for the author to try to guess which parts of their manuscript need amendment.

- Be shy. You were chosen to review the manuscript because you have the expertise to provide useful feedback

- Get distracted with spelling and grammatical errors. (If the manuscript is accepted for publication, a copyeditor will fix mechanical issues.)

- Be rude or offensive.

Comments to the Editor

The peer reviewer’s comments to the editor are confidential and will not be available for the authors to read. You must be frank about your opinion and comment on whether you think the manuscript is worth publishing. There is no need to repeat comments intended for the author from the prior section here, however, major flaws or ethical issues may be re-emphasized. Furthermore, you may want to declare any conflicts of interest in this section, or your inability to review certain parts of the manuscript.

The message conveyed to the editor in this section should be compatible with the message you are trying to convey to the authors. If your comments to the author indicate only minor revisions but your comments to the editor identify very significant concerns about the manuscript, for example, these conflicting messages will create a communication problem, making it more challenging for the editor to make a decision.

Submitting the Review

This is the final step of the review process. Re-read your review to make sure it is clear, valid, and courteous. Next, reflect on the review questionnaire and score each section (if applicable). Finally, make a recommendation for publication. Once your review is submitted, the editor assigned to the manuscript will ultimately make a publication decision. The journal’s editor in chief will then approve that decision and relay it to the authors.

Summary

Peer review is a crucial part of scientific research and depends on the intellectual exchange of thorough and productive feedback amongst experts in the field. Therefore, delivering a well-defined, comprehensive, and constructive review report is essential to the peer-review process. Engaging in peer review can be a highly gratifying experience that can also benefit the reviewer’s own research and academic career. In summary, there is little to lose and a lot to gain from being a reviewer.

Peer Review Resources

- Wiley’s Step by Step Guide to Reviewing a Manuscript

- Committee on Publication Ethics’ Guidance

- Nature: Focus on Peer Review free online course

Table 1. Guidelines and Checklists for Different Study Types.

|

Study Type |

Guidelines |

Source |

|---|---|---|

|

Randomized controlled study |

|

|

|

Observational study |

|

|

|

Systematic review/meta-analysis |

|

|

|

Study protocols |

|

|

|

Biomarker study |

|

|

|

Diagnostic/prognostic study |

|

|

|

Case report |

|

|

|

Clinical practice guidelines |

|

|

|

Qualitative research |

|

Dr. Abdou recently completed her hematology/oncology fellowship at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center. She has accepted a faculty position as an assistant professor at the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center focusing on breast cancer immuno-oncology and cancer immunotherapy. She served as the Journal of Clinical Oncology editorial fellow in 2019, mentored by Dr. Bruce Haffty. Follow her on Twitter @YAbdouMD.

Comments

Flavia Rocha Paes, MD

Aug, 01 2020 7:44 AM

Excellent post!!! It shows us step by step to write a relevante peer review.