By Julia Close, MD

By Julia Close, MD

“When is the best time to have children?”

The question, arising from an eager medical student at a forum where I was a panelist on work-life balance, was not unexpected.

As men and women are now equally represented in medical schools, the physician mom is no longer rare. Many of us carry this title. None of us is perfect at balancing the demands of motherhood and medicine. (If you are, PLEASE, for all us, contact ASCO immediately and write a blog post about it!)

I asked the same question while I was in medical school. I understand the dilemma. Most of us in medicine are planners. From the age of 8, I planned to be a doctor. I had a vision of myself, smartly dressed, in a lab coat, saying lots of smart medical things, saving lives, working long hours. I also planned to be a mom, smartly dressed, in mom jeans (I planned this before Lululemon existed), saying lots of smart maternal things, making cookies from scratch, picking kids up from school. I never imagined the two pathways intersecting.

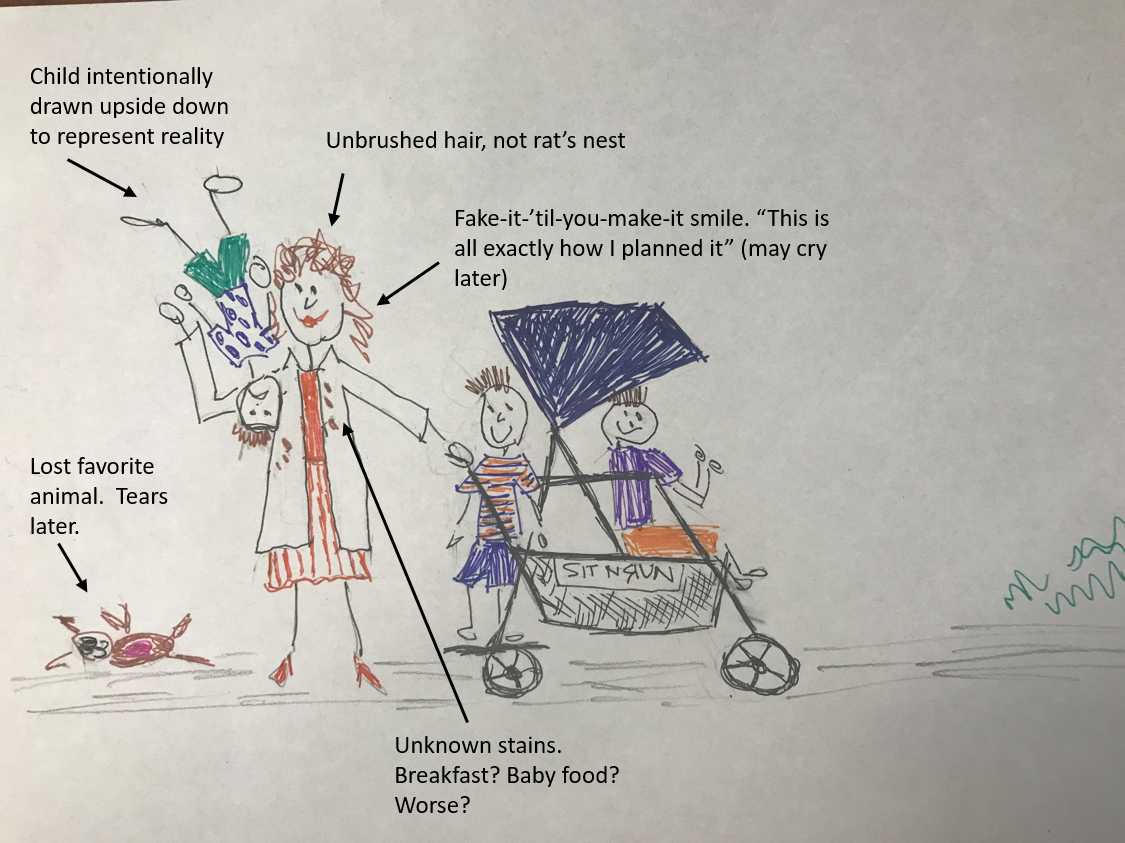

The reality of being a mom and a physician contrasts to the description above, as depicted in the image below. This is me, when my boys were 0.5, 3, and 4 years old. My university employer offers onsite daycare (kudos to the University of Florida). As faculty at the time my third child was born, home-based help was financially an option. Our older two were already in daycare, and the desperate run to get there before closing (sometimes a full-on sprint) helped to ensure that at least my husband or I, and hopefully the children, arrived home at a “reasonable” hour. We chose to keep all three at the same center. I managed to wrangle the menagerie into a sit-and-stand stroller for the pickup and drop-off ritual. Occasionally, one of the ambulatory boys would not want to ride. My usual approach, after an attempt at negotiation, was to place the rebelling child on my shoulder, often kicking and screaming, and proceed as scheduled. This was usually when I passed stately professors who had taught me in medical school, who either failed to recognize me or stared at a suddenly important mole on their left hand, thereby avoiding the train wreck that was passing them on the crosswalk.

Life as a physician mom is often messier and louder than planned. I mostly hold back the gory details when talking to the bright-eyed women who have yet to have children. I’m not trying to scare them.

Before I had kids, I had my career mapped. I had forgotten to pencil in my life.

My husband is also a physician. We married intern year and inevitably began to discuss when we should have children. He suggested “when have more time and more money.” Looking ahead to residency, fellowship, and life as an oncologist, then reflecting on our student loans, it appeared these criteria could be met in retirement. Spoiler alert! In this post there is only one definitive statement regarding women physicians having children, and here it is: retirement is NOT the optimal time to have a baby.

So when is the best time?

A recent study by Krause et al1 looked at evaluations of residents (both men and women) by residents before, during, and after pregnancy. They found that mean peer evaluations were lower after pregnancy for female residents, regardless of the gender of the evaluator. Faculty evaluations of the residents during the same continuum were not affected.

As a program director, I have made similar observations. Women residents who have children during training are often described as not being team players. The supporting evidence: she did not volunteer to cover call, she used sick leave, she left the hospital earlier than others. What I don’t hear mentioned is work left undone or inappropriate care of patients. When querying faculty that have worked with the same house staff, they note no deficits in knowledge or work ethic.

Do these data suggest that residency is not the right time to have a baby? Absolutely not.

These data suggest there is room for improvement in the environment. As the authors point out, the mean maternity leave for internal medicine residents was 6.1 weeks in 2014, compared with 10.3 weeks for the general population of employed women in the United States. As the difference in evaluations was noted for peers, but not supervising faculty, further studies are needed to determine what can be done to improve colleagues’ interactions after pregnancy. I suspect what house staff returning to work after pregnancy need is more support—child care options, especially after hours and for children who are sick, places to comfortably and conveniently pump, and more options for maternity leave, to name a few.

Steps are being made in the right direction. The most recent suggested revisions to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medicine Education (ACGME) common program requirements included a requirement for clean and private facilities for lactation, something many institutions increasingly offer, along with onsite daycare.

I do not know of data regarding how pregnancy impacts the evaluations of fellows in hematology/oncology, although it is reasonable to hypothesize similar review of evaluation data may be found.

My husband and I planned to have our first child during the (generally) night- and weekend-responsibility-free year that I was chief resident. Despite our best efforts to control the science of conception, I did not get pregnant until my first year as a hematology/oncology fellow, giving birth at the end of that year. Six months later, I found myself pregnant again. For the record, difficulty conceiving at one point in your life does not always mean it will be difficult later—lesson learned. I was faced with telling my program director and colleagues that I was pregnant again. I felt irresponsible, like I would not be taken seriously as I had chosen to distract from my training in this way. I felt like a burden on my colleagues.

Our childcare costs consumed nearly my entire salary (after taxes).

I had placed myself in the position of interviewing while on maternity leave, asking practices composed of all or nearly all men for a place to pump (specifying, not in the bathroom) while interviewing. There was no hiding I had (at least) one young child, opening myself up to bias from a future employer about my ability to manage a demanding job concurrently.

With all of the above, do I recommend against having children while in training? Considering the career timeline, waiting to have children until starting in practice makes it difficult (biologically speaking) to have more than one child. The first few years in practice can be just as hectic as training. Finances may be better off, but responsibilities are often more demanding.

So how did I answer the “when is the best time?” question when most recently asked? I gave a long answer—that there is no perfect time. The cost of childcare is high, so be prepared. Also, the cost to your career exists, but can be mitigated. When you are ready, dive right in. Being a mother to three boys is the greatest adventure I have ever been on.

Taking all of these factors into consideration, what can an individual do to reduce the career impact of having a child?

- Set your own priorities. I respect physician women who choose to step back for a year or two (or 10), as much as I respect those who press forward. What is right for one woman may not be right for you.

- Look for a supportive environment. Are there other women? Find an inside source to query about policies and politics. I wish I could say that you can ask openly regarding maternity leave without conversations behind closed doors occurring later which may impact your career. In some environments, just asking may reduce your chance of employment. Another good question to ask yourself: do you want to work somewhere that this occurs? Perhaps openly asking about policies is exactly what you should do. This is a personal choice to consider.

- Accept help! It takes a village—find one and use it.

What can we do to support the women around us?

- Respect each other’s choices about priorities regarding work and children.

- Never assume someone is not ready for advancement because of a recent child—as above, that is a personal choice. Some of the best administrators I know are pumping in their offices!

- When in a leadership position, question comments from others about the same—having children does not make someone less prepared for or dedicated to advancement. Maternity leave is necessary, but in the big picture it is not that long!

- Advocate for onsite childcare, availability of pumping sites, and work adjustments for women as they transition back to work from maternity leave.

- Advocate for formal parental leave policies.

What is your advice on this question? Has your answer changed over the years?

Dr. Close is a clinical associate professor at the University of Florida, where she is the program director of the Hematology/Oncology Fellowship Program. In addition to education, she is focused on performance improvement as the assistant chief of medical service in the Gainesville VA Medical Center.

Reference

- Krause ML, Elrashidi MY, Halvorsen AJ, et al. Impact of pregnancy and gender on internal medicine resident evaluations: a retrospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:648-53.

Comments

Carmen Julia Calfa, MD

May, 19 2018 2:49 PM

So beautifully written and so relevant!

I agree with Julia. There is no "perfect time" to be pregnant or have children.

Define your priorities, make a team with your partner/ spouse, invest in getting the right help, work hard and feel good about it!