Aug 18, 2016

By Jack Lambert, Staff Writer

Perhaps more than any other book in recent memory, When Breath Becomes Air has struck a chord among readers, both inside the medical community and among the public, desiring an honest and philosophical consideration of death.

The autobiographical account of Paul Kalanithi, MD, a physician diagnosed with lung cancer, has been a mainstay on The New York Times bestseller list. His widow, Lucy Kalanithi, MD, has traveled the country talking to patients and physicians about the book and her late husband’s legacy.

When Breath Becomes Air was selected for ASCO Book Club at the 2016 Annual Meeting. Dr. Lucy Kalanithi, a clinical assistant professor of medicine at Stanford University, spoke at the book club session in a discussion moderated by Teresa Gilewski, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

AC: There is a particular genre of books about cancer that your husband describes eloquently as “exhortations to gather rosebuds.” When Breath Becomes Air does not belong to this genre. Instead, the book is a meditation on the meaning of death and life. Why did he write it this way?

LK: He wrote it that way because he lived it that way. You can tell from the book he had this background in literature and philosophy. Even as a healthy young person in his twenties, he was interested in death as a philosophical problem. When he got his stage IV lung cancer diagnosis at age 36, he had already seen death multiple times as a neurosurgeon and neurosurgery resident. He had come to understand his role as not only fighting death, but also shepherding people all the way through toward their death and helping them cope.

When he ended up with a [cancer] diagnosis, he was particularly prepared to meditate on it. He already had a language and a way to think about it. It’s such an intensely personal and emotional topic, but he was able to step back and look at it.

The interesting thing about death is that it is looming throughout the diagnosis and treatment of serious or terminal illness, even if we are not talking about it. The response that Paul’s book is getting from the public, as well as the letters I am getting from patients and oncologists, shows that people are hungry to talk about mortality—and meaning—in a real way.

My experience in the lung cancer patient community is that death is looming. It is on people’s minds. Even if patients are not explicitly talking about it publicly or openly, they are still thinking about it. Being prepared and having an outlet to talk about dying is healing. It lets people know that things will be okay, even if they are not okay.

AC: Your husband writes, “The secret is to know that the deck is stacked, that you will lose, that your hands or judgment will slip, and yet still struggle to win for your patients. You can’t ever reach perfection, but you can believe in an asymptote toward which you are ceaselessly striving.” How should oncologists reconcile these notions: the mortal responsibly they assume for their patients and the unfavorable outcomes that often result from treatment?

LK: Paul loved and needed his oncologist so much, and it was not because he thought she was going to cure the disease. He knew she couldn’t. No one could, and that wasn’t a failure of hers. Instead, he trusted her guidance around how to make sense of the illness and to focus on his values and priorities despite being sick.

She kept all the options open for him, so even though he had stage IV lung cancer, she thoughtfully designed his chemotherapy regimen so that he could still be a surgeon. He came to realize that what she was doing was helping him live as he died, which was such a gift.

AC: Given your and your husband’s familiarity with and understanding of medicine, why did his oncologist refuse to discuss his Kaplan-Meier curves? Was that a symbolic decision?

LK: It’s hard to exactly know because we looked up the curves; we knew they applied to him. We knew it was factually more probable that he would die within a few years, certainly within 5 years.

That information was really important to us when we were making decisions, like if he should go back to work, how long he should keep working as a surgeon, or if we should have a baby. We didn’t do any of that to spite cancer. We did it with our eyes fully open, including me understanding that I would be a single parent. That information was really necessary for us to make those decisions.

I think the message that Paul is sending in the book was that by ignoring his question, his oncologist made him find his values and live according to his values, no matter how much time he had left. It was such a gift for her to do that as a physician.

Writing the chemotherapy orders was the least important part of her job. She was engaging with him as a human being, which was just so powerful to him. It brought him back to life, in a way. Even when he was dying, it helped him live.

AC: Your husband discusses the importance of understanding life through experience, even before he was diagnosed with cancer. Is it possible for oncologists to fully understand their patients without having lived through the experience?

LK: As a physician, you don’t have the benefit of having experienced [an ailment] yourself, but you do have the benefit of having seen it multiple times, which is something patients don’t have. Paul describes it as the “experiential landscape”—here’s what the road looks like stretching forward and here is how we can make our way through this, or to the end of it.

Going through this experience made me more attuned to my own patients when trying to describe what things would feel like. I don’t minimize things like side effects anymore. Instead, I describe what patients are likely to feel as they take a type of medicine.

AC: The book describes how the career path of a physician often sees the payoff of their training—in terms of salary, prestige, and work-life balance—toward the end of their career. Did Paul view his career trajectory that way?

LK: Regarding medical training, in her review of Paul’s book in The New York Times, Janet Maslin wrote, “By the time he was ready to enjoy a life outside the operating room, what he needed to learn was how to die.”

I think Paul would have taken issue with that. He felt like his neurosurgical training was his life. He was living and the meaning he was getting from those interactions, even though he was a trainee, was so deep. As physicians, we must understand that there is gratification to be found today, not just delayed gratification, if you’re present. The meaning of what you’re doing in your medical training, whether you are a student or a resident, is huge no matter what you’re doing. You are impacting people’s lives.

Paul didn’t have regrets about dying at the end of his training. All you can do is make the best decisions you can in the moment and you never know how much time you have left. Thankfully, he was proud of the trajectory he came through.

AC: What surprised you the most about having a loved one diagnosed with cancer?

LK: The main thing is how difficult it has been since Paul died. He talks in the book about how, for him, the future evaporated. That happened for me personally after Paul died.

The future shrank down when Paul was alive, but when I was taking care of him I felt so purposeful. When he died, it was like, “Does my life just get rebuilt into what it used to be? Or am I also charting a new life?” And it turned out to be the second one.

That shift in identify when someone dies is not limited to losing them. It is losing your whole identity, too. It’s even something as simple as missing Paul’s oncologist. We saw her every other week for almost 2 years. When Paul died, I sent her flowers. I love her. I am so grateful to her and I miss her. That depth of gratitude didn’t surprise me, but that feeling of wanting to be connected is really profound.

AC: What was it like participating in the ASCO Book Club and sharing Paul’s story with a group of oncologists?

LK: I had a chance to sit on stage for ASCO’s Book Club and talk about our experience of being two married physicians who suddenly became a patient with cancer and a caregiver.

Terri Gilewski started out by describing Paul’s clinical course: “A 36-year-old man with no past medical history presents in May 2013 with 6 months of back pain and unexplained weight loss followed by a cough and is diagnosed with stage IV EGFR+ pulmonary adenocarcinoma metastatic to bone. He does well on erlotinib for 10 months and then progresses and starts carboplatin/ pemetrexed/bevacizumab. He is subsequently hospitalized twice for complications of chemotherapy. After 9 months of stable disease, he progresses further despite a brief response to afatinib/cetuximab and develops persistent nausea and subtle dysarthria; he is found to have new brain metastases and leptomeningeal disease. During the washout period for a clinical trial, he has rapid disease progression with acute-on-chronic respiratory failure. Despite 14 hours on BiPap, his ventilatory status continues to worsen. During a discussion of his goals of care, he chooses to forego intubation. He transitions to comfort care and dies shortly after, in March 2015.”

But right after that presentation, she said, “And now we’re going to talk about all the things that aren’t summarized in the clinical case presentation,” meaning our return to work as physicians, our decision to have a child during Paul’s illness, what it felt like to make those personal medical decisions, grief, and the response to When Breath Becomes Air, Paul’s writing about facing his mortality as a physician, a patient, and a lover of literature—and about the physician-patient relationship.

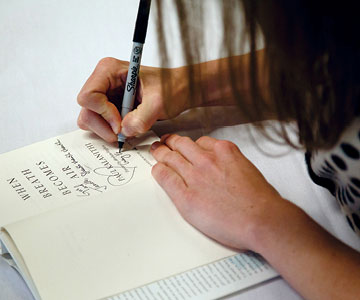

Even though I’m doing a national book tour [on behalf of] my late husband, I was nervous to present at the ASCO Annual Meeting. I remember when Paul’s oncologist went out of town in 2013 and 2014 to go to ASCO. I felt such profound respect and gratitude for the crowd. It was gratifying for me to hear the audience share their personal struggles—with prognosticating for patients, with end-of-life decisions, with their own or family members’ illnesses— and then to sign books. It was a highlight among what have been the worst and best years of our lives.