Aug 26, 2014

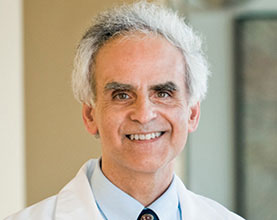

Stephen A. Cannistra, MD, FASCO, on the wonders of astrophotography

|

|

| Stephen A. Cannistra, MD, FASCO Institution: Director of Gynecologic Medical Oncology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center; Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School Specialty: Gynecologic cancers Member since: 1986 ASCO activities: Journal of Clinical Oncology Editor-in-Chief, Ethics Committee |

|

What keeps Journal of Clinical Oncology (JCO) Editor-in-Chief Stephen A.Cannistra, MD, FASCO, awake at night? Galaxies, nebulae, and supernova remnants, typically. Despite a full scheduleof professional responsibilities as the Director of Gynecologic Medical Oncology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School, on clear nights, Dr. Cannistra will drive 50 miles to escape Boston’s light pollution and pursue his passion of astrophotography: creating detailed images of distant objects in space, which he shares on his website, starrywonders.com.

AC: When did you become interested in astrophotography?

Dr. Cannistra: When I was young, I received an inexpensive department store telescope and started exploring the night sky. I was enamored by Saturn, the ringed planet. Once yousee Saturn in a telescope, even a small telescope, you are hooked!

Over 10 years ago, I decided to delve into astronomy more seriously—not just doing visual observation through a small telescope, but really trying to understand what’s out there using more sophisticated equipment. The long-exposure photos you see of faint objects in space, compared to what you actually see with your naked eye in a telescope, are very different. Looking at a faint object like a nebula throug the telescope, you typically just see a fuzzy blob that doesn’t look anything like the same object portrayed in astronomy magazines. On the othe rhand, if you have the right equipment that will allow you to take a long-exposure photograph, that fuzzy blob comes to life and reveals all the inner glory of a galaxy or nebula.

But you can’t just take a telescope and put a camera on the end of it—in addition to good equipment, you need a solid understanding of visual astronomy, how a telescope mount works, the optics of the telescope, and the computer software that controls the camera and telescope. Combining all of these facets of astrophotography is what excites me. I’ve even developed software that allows me to control things like the exposure time and the telescope’s motion throughout the imaging session.

Astrophotography combines my interests in the night sky, photography, computer science, and software development—all packaged into one hobby.

AC: From start to finish, what goes into taking an amazing picture of a faint object in space?

Dr. Cannistra: Whenever the sky is clear, I travel an hour to my old homestead in rural Rhode Island, where I keep my equipment. I set up the equipment, including polar aligning the mount, and connect everything from scratch each time, which takes about an hour. I usually plan for an eight- to 10-hour total exposure for a given object, but sometimes longer, in which case I need to image over several nights. Because the objects are so faint, you have to keep the camera shutter open for long periods of time to catch enough photons to actually see them. The telescope is on a mount that tracks the object through the sky while the Earth rotates, using a path set by the computer. Up until about five years ago (when this kind of software became available), I would have to stay up all night to babysit the telescope, but now I can go home and get some sleep while the telescope does its job. This means that I have enough energy to do all of my JCO work the next day!

After the exposure is finished, the image requires quite a bit of processing. At the end of session, I end upwith 20 to 30 subexposures of about 20 minutes each in length. I use specialized software to combine all of the subexposures into one master file, and at that point, I’m left with a raw image which is still pretty faint. I then use image processing software like Photoshop to enhance the areas of the image that are difficult to appreciate .It takes about six to eight hours of processing to really get it right. I use the actual colors recorded by the camera and enhance them enough to bring out the object’s inner beauty.

It’s very exciting to see an object come to life as you start processing it and discover details that you couldn’t se ewith your eyes through the telescope.

AC: If you had the opportunity to be a “space tourist” and see some of the objects you’ve photographed, would you take it?

Dr. Cannistra: I wouldn’t. Even if I could travel very close to the Great Andromeda Galaxy, it would actually look quite drab. If I were close up to the Cygnus Loop, it would just look like a few ghostly shadows. My eyes are not nearly as good at collecting photons as the chip in my CCD camera—with my eyes, I would only be able to see in space maybe 5% to 10% of what I can capture in a long-exposure photo here on Earth.

AC: When did you begin submitting your photos for publication?

Dr. Cannistra: About eight years ago, and it’s taken off since then. In addition to publishing photos, I’ve contributed to book chapters, and I’ve given talks at astrophotography meetings, such as the Advanced Imaging Conference in San Jose. I’ve developed my own special processing techniques, which are now used by other astrophotographers around the world.

AC: What is it about astrophotography that inspires such a powerful commitment?

Dr. Cannistra: The magic of exploring the sky, for me, is not simply related to discovery and being inquisitive, but it makes me realize how big the universe is and how small we are. It helps me place myself and the things we do here on Earth into context. It’s a way to become humble with oneself and to be inspired by the wonderful processes that have led to the creation of the stars, our solar system, and life on Earth.

A Tour of the Universe with Dr. Cannistra

Below, Dr. Cannistra outlines some of the unique details captured in his latest images, in which stars are born and then explode and die. “These dynamic processes are occurring within our universe all the time,” he said.

|

| Great Andromeda Galaxy “The Great Andromeda Galaxy is a favorite object of many astrophotographers. It’s about 2 million light-years away from our own Milky Way galaxy. You see blue on the edges and a reddish-orange hue in the core. The reddish color in the core represents light emitted from older stars, as well as selective attenuation of blue light by central dust, leaving only the red light to penetrate through the core (similar to the reason why our sunsets are red). The blue in the periphery comes from high-energy light (emitted in the blue region of the visual spectrum) typical of new stars that are being formed in the galaxy’s outer rim.” |

|

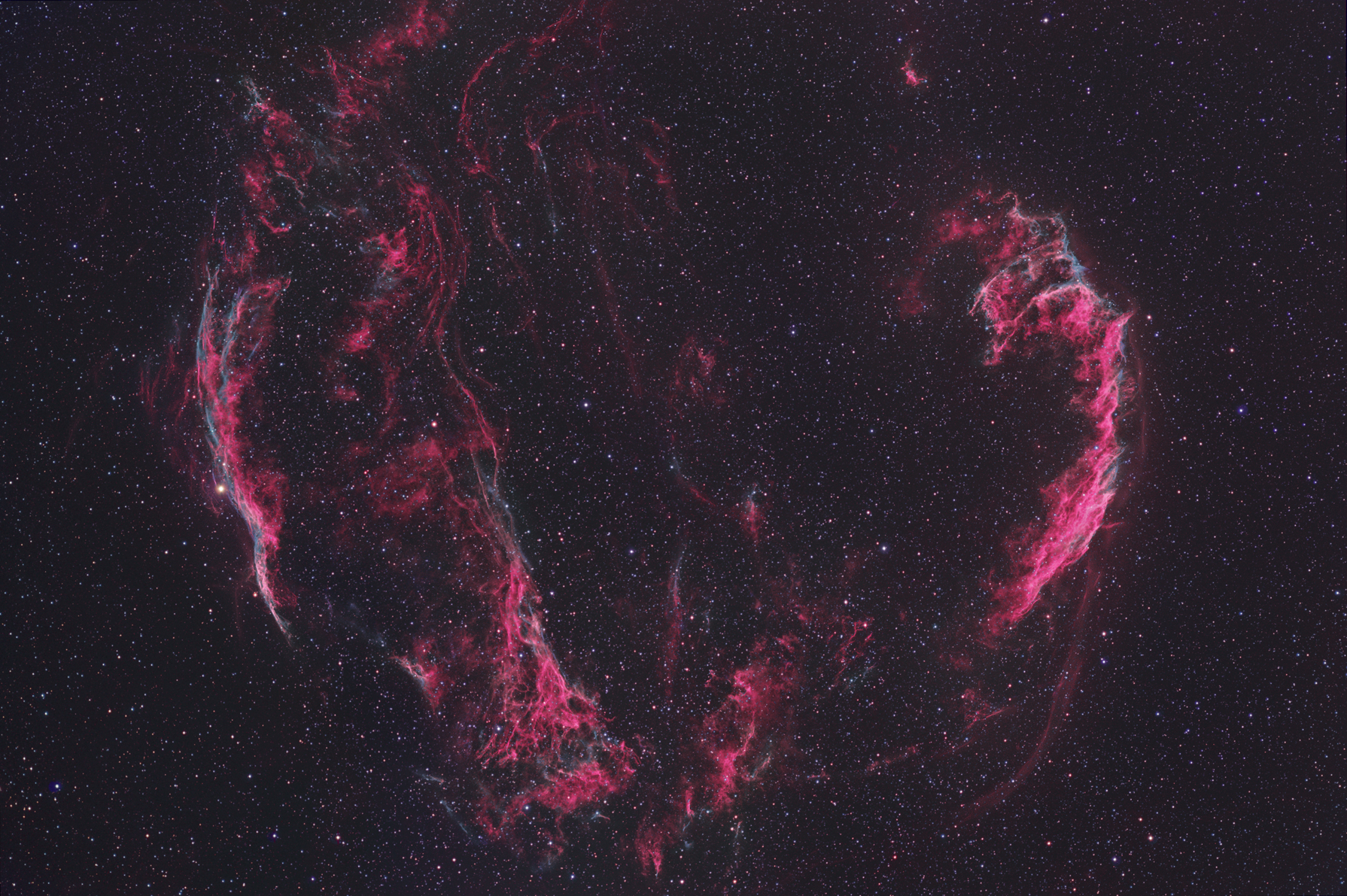

| Cygnus Loop “Here you see a messy jumble of tendrils and diaphanous filaments. The red comes from hydrogen excited by high-energy ultraviolet radiation emitted by a nearby star. The blue comes from oxygen being excited by the same process. It’s interesting to be able to say something about the chemical composition of a nebula simply based upon the types of color sthat it emits. The tendrils represent the explosion of a star that was in the process of dying thousands of years ago. As the star died and exploded, it shed gases out from its center to form a shell—a supernova remnant. What we see here are bits and pieces of ionized gases that are especially prominent at the edges of the expanding shell.” |