Oct 23, 2017

Are Doctors and Their Patients Protected From Future Shortages?

By Lindsay Pickell, ASCO Publishing

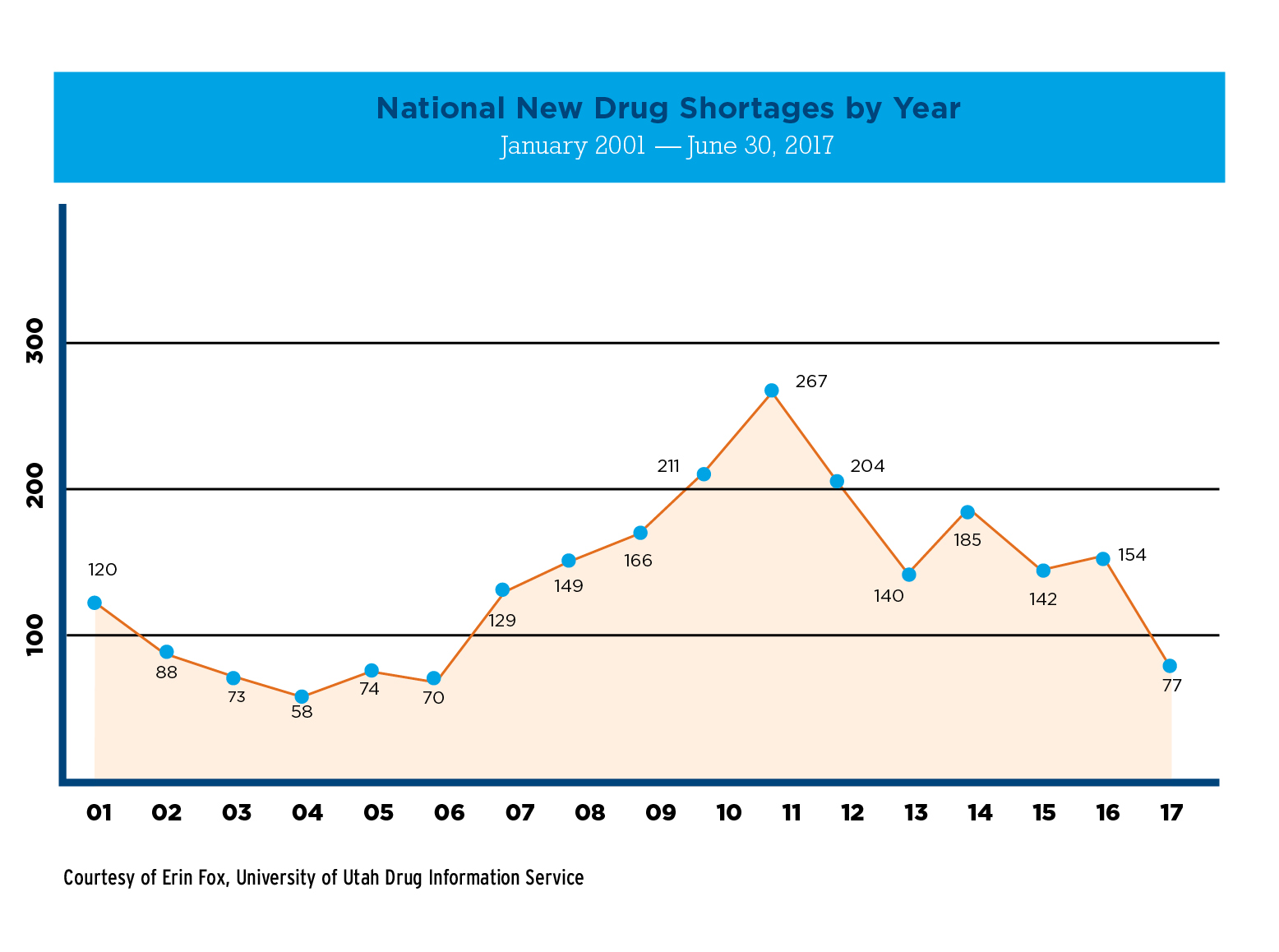

At the height of the drug shortage crisis in 2011, the number of new drugs in shortage more than tripled, from approximately 74 in 2005 to 267 in 2011. These drugs were primarily older, generic, injectable drugs like methotrexate, norepinephrine, and morphine—drugs that are lifesaving, but also produce slim profit margins for manufacturers.

Patients bore the brunt of the shortage’s consequences. Some had their treatment delayed, some were required to pay exorbitant out-of-pocket costs for brand-name substitutes, and others risked unknown and potentially harmful effects from alternative treatments. Alternative treatments used during drug shortages are correlated with higher rates of medication errors, side effects, disease progression, and deaths. An analysis of a study of children with Hodgkin lymphoma treated with a regimen prescribing mechlorethamine revealed that patients treated with cyclophosphamide in place of mechlorethamine (during the period when mechlorethamine was unavailable) experienced significantly worse outcomes. Two-year event-free survival was 88% for those treated with mechlorethamine compared with 75% for cyclophosphamide.1 A recent study published in JAMA showed that the 2011 norepinephrine shortage was significantly associated with increased mortality among patients with septic shock (35.9% during normal use vs. 39.6% during shortage).2

“We were totally blindsided by how vulnerable the drug supply was,” said Michael P. Link, MD, FASCO, of Stanford University. Dr. Link served as 2011-2012 ASCO President, during the height of the shortage, and also authored the study concerning mechlorethamine.

The impact of the drug shortage crisis extended beyond the patients who were not able to receive the treatments they needed. Estimates put the cost of shortages to health care systems at $200 to $300 million per year as a result of gray market price gouging and the increased infrastructure required to manage shortages.3 In 2011, more than 200 clinical trials funded by the National Cancer Institute depended on a drug in shortage, and patient accrual in many trials was delayed. “Beyond affecting immediate patient care, this crisis is stalling progress at a time of great promise in cancer research,” W. Charles Penley, MD, FASCO, who served as the 2011 chair-elect of ASCO’s Government Relations Committee, said during testimony at a 2011 hearing of the House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Health.

To confront the crisis, public health organizations and institutions rallied on Capitol Hill in a series of public workshops, hearings, and briefings to engage policymakers and appeal for intervention from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). ASCO played a significant role in these efforts by issuing recommendations to ease shortages, collaborating with key stakeholders such as the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) and American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), supporting legislation designed to address shortages, and sending representatives such as Dr. Penley to testify in front of legislative committees. These efforts resulted in an Executive Order by President Obama in 2012, directing the FDA and Department of Justice to take action to reduce and prevent drug shortages.

Status of Life-Sustaining and Lifesaving Generic Drug Availability in 2017

The Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA) went into law on July 9, 2012. The FDASIA gave the FDA important new authorities to combat the primary causes for shortages: raw materials, manufacturing quality issues, delays related to quality and capacity, loss of manufacturing site, increased demand, and discontinuation. These authorities include mitigation tools to expedite FDA inspections, exercise temporary flexibility for new sources of medically necessary drugs, and allow use of sterile filters for individual batches of a drug initially not meeting established standards to be released, among other abilities.

Most importantly, however, the FDASIA requires manufacturers to notify the FDA of a discontinuation or interruption in the production of drugs that are “lifesaving, life-sustaining, or intended for use in the prevention or treatment of a debilitating disease or condition.” The FDA makes these manufacturing notifications public, as well as updates the supply status via their Drug Shortage Database. Additionally, the FDA has developed a new reporting platform for manufacturers, CDER Direct, and a mobile app to speed public access to valuable information on current and resolved drug shortages and discontinuations of drug products.

“FDA has been very good about sharing what information they can about potential or existing shortages, and whether or not a shortage is going to be short or long term,” said Joseph Hill, ASHP’s director of government relations. ASHP’s website provides information on real-time shortages collected by the University of Utah Drug Information Service (UUDIS). Their inclusion criteria varies slightly from FDA’s and reflects shortage status at the health care provider level. This article reports ASHP/UUDIS shortage data unless otherwise noted.

The new authorities granted to FDA have produced encouraging results. Since 2012, shortages have been trending down. In 2016, there were 154 new shortages and an average of 184 active shortages. As of this writing, there are 77 new shortages and an average of 175 active shortages for 2017. The FDA reports that in 2016 it prevented 115 shortages of all forms of drugs and 87 shortages of injectables.

“We Still Have a Problem”

Although the number of new shortages has decreased, long-term active and ongoing shortages are not resolving. In their 2016 report on drug shortages to Congress, the FDA acknowledged, “shortages continue to pose a real challenge to public health.”

Seven chemotherapeutic agents currently are in shortage: injectable bleomycin sulfate, dexrazoxane, ethiodized oil, etoposide phosphate, leucovorin calcium lyophilized powder, methotrexate sodium, and asparaginase Erwinia chrysanthemi—a drug crucial to the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in pediatric patients who become hypersensitive to E. coli–derived asparaginase.

Equally troubling, if not more so, are the current shortages of basic supportive care drugs, like vitamins and electrolytes needed for parenteral nutrition, intravenous saline solution, and sodium bicarbonate, which is required to administer high-dose methotrexate.

“We still have a problem,” Dr. Link said. “Even though the number of chemotherapeutics in shortage has decreased, we oncologists continue to have our hands tied because of shortages of other basic drugs.”

Threats to Current and Future Drug Availability

Manufacturing. Manufacturing continues to be the most significant reason why shortages have not been resolved. According to a 2016 study by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), shortages, especially shortages of sterile injectables, are “generally traced to supply disruptions caused by manufacturers slowing or halting production to address quality issues.”

The GAO also found that facilities linked to widespread shortages tend to be serial offenders. During the 2011 crisis, seven sterile injectable drug manufacturing facilities received FDA warning letters for noncompliance with manufacturing standards. Those facilities thus slowed or shut down production, which resulted in shortages. As of April 2016 (the latest available data), five of these seven establishments continue to cause shortages.

“FDA has been able to prevent more and more shortages, but most drug shortages are due to a manufacturing or quality problem at the factory,” said Erin Fox, PharmD, BCPS, FASHP, senior director of the UUDIS. “There is nothing the FDA can do to fix those issues. That is on industry.”

Issues like facility consolidation through mergers, acquisitions, and closures as well as secrecy around the specific facilities in which drugs are made compound manufacturing’s impact on drug availability. Sanofi has discontinued BCG, the mainstay treatment for bladder cancer, and will stop shipping the drug to the United States later this year. Merck will become the only U.S. supplier of BCG, which has to be grown under very stringent conditions to avoid spoiling.

“We want to have multiple people making challenging drugs, biologics in general, because that way we know the drug will be available,” Benjamin J. Davies, MD, of the University of Pittsburgh, told Urology Times in a recent interview. “If Merck’s one plant in North Carolina goes down, even for reasons of which it really has no ability to control, what do we do?”

Drug pricing and reimbursement. The responsibility of safeguarding the integrity and supply of drugs so that U.S. patients aren’t put at risk is ultimately left to manufacturers. However, the low profit margins of the generic drugs most commonly in shortage provide little incentive for manufacturers to invest in facility modernization, increase production when competition withdraws from the market, or enter the generic drug market to begin with. Low generic drug profits and manufacturing issues are so entwined with shortages, it resembles a chicken/egg paradox.

“Some medications that have been on the market for 20 to 30 years have only one supplier, and, in some cases, these suppliers behave like a brand company where they price their drugs at whatever the market will bear,” Mr. Hill said. “That’s not the intent of creating the generic marketplace. It was supposed to be one in which there was robust competition driving prices lower.”

Changes in reimbursement to Medicare Part B, expansion of Medicaid 340B, and creation of Medicare Part D as part of the Medicare Modernization Act (MMA) have also affected generic drug prices and, thus, supply. According to a 2017 analysis, the 50% drop in drug reimbursement resulting from the MMA led to about 16 additional days of shortages for generic injectables. A 1% decrease in price ($0.32 cents per unit) led to 0.40 more shortage days for off-patent drugs.4

International supply. Part of the FDA’s ability to curb shortages relies on its flexibility to import drugs from international suppliers. But recent reports show that the international supply isn’t as stable as it once was.

The European Society for Medical Oncology found that shortages have become more commonplace in the last decade and estimates that about half of European hospital pharmacists have experienced shortages of cancer drugs, mainly generics such as fluorouracil, cisplatin, and methotrexate.

And although European Union drug pricing models place generics at slightly higher prices than in the United States, they aren’t spared from price gouging and market manipulation. The European Commission is formally investigating Aspen Pharma for increasing the price of five cancer drugs by several hundred percent.

Many hospitals in Canada experienced shortages of fluorouracil earlier this year after Accord Healthcare, which supplies 55% of the drug in Canada, was temporarily shut down for investigation of a shipment of leaky vials. This shortage coincided with enforcement of amendments to Canada’s Food and Drug Regulations mandating drug authorization holders to publicly report drug shortages and discontinuations.

Current shortages abroad aren’t as critical as what the Unites States encountered in 2011, but the stability of international drug supply impacts effective shortage resolution in the U.S. It is certainly not a safety net.

“We can’t let our guard down,” Dr. Link said. “We are always one manufacturing error away from a critical shortage.”

Current Organizational Level Efforts to Minimize Shortages

Since 2012, most health organizations have taken a “wait and see” approach to allow manufacturers time to adapt to the FDASIA’s new regulations and to analyze the long-term trends. ASCO has been actively monitoring publicly reported industry activities that could disrupt supply (such as facility closures, consolidations, and quality issues) and drug shortage lists from the FDA and ASHP.

But now, ASCO and partner health organizations, such as ASHP, ASA, the American Heart Association, and the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, are mobilizing. These are the same organizations that prompted change in 2011 and 2012, and they are hoping to do it again.

ASCO and its partners are engaging in preliminary discussions to ensure progress is sustained and continues to be made. Some of the topics they are discussing include how to help the FDA with its backlog of applications for generics, to determine if manufacturers can supply more information on quality during disruptions, and to recommend ways to increase competition or stabilize prices to add resiliency to the market.

The end goal would be for ASCO and stakeholders to open new talks with FDA to determine further solutions to continue the downward trend.

References

- Metzger ML, Billett A, Link MP. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2461-3.

- Vail E, Gershengorn HB, Hua M, et al. JAMA. 2017;317:1433-42.

- Kaakeh R, Sweet BV, Reilly C, et al. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68:1811-9.

- Yurukoglu A, Liebman E, Ridley DB. Am Econ J. 2017:9:348-82.

Resources

View the ASHP’s lists of current drug shortages, resolved shortages, and discontinued drugs, and get advice on how to look outside normal supply chains for drugs

Report a drug shortage to the FDA and request a current list of drug shortages

Report price gouging or gray market activity to FDA’s Office of Criminal Investigations

What Can Oncologists Do to Minimize the Impact of Shortages on Their Patients?

There are several actions that physicians can take to minimize the impact of current shortages as well as future ones.

Be proactive and have protocols in place when a shortage occurs. Oncologists and health care professionals should make sure that their institution is prepared to deal with shortages and subsequent drug rationing practices. Most practices and hospitals have existing ethics committees, and any cases of drug rationing should be brought directly to these committees to ensure fair use of medications. If a practice does not have a committee, they should set transparent protocols based on objective criteria for how to treat patients who require drugs in shortage.

Report shortages, purchase on quality, and avoid gray market sellers. Hospitals and pharmacies should always report shortages directly to the FDA; sometimes this is the agency’s first notification of a shortage. Staff who are responsible for purchasing medications should also make an effort to purchase the highest quality products. “We spend millions on medication,” Ms. Fox said. “The more we decide to purchase on quality, the more we incentivize manufacturers to make quality products.”

When shortages occur, unknown distributors may offer these drugs at higher prices than the pharmacy or hospital would normally pay. Gray market sellers take advantage of hospitals by price gouging or by selling drugs that have expired, were diverted, or may be counterfeit. The best way to avoid gray market sellers is to “always know your supplier,” according to Mr. Hill.

The Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA), enacted in 2013, helps hospitals and pharmacies know from whom they’re buying. Also known as “Track and Trace,” the DSCSA requires documentation of certain drugs every time they change hands. The DSCSA has marginalized the ability of the gray market to operate, but health care professionals should still be aware of this practice and inform the FDA’s Office of Criminal Investigations if solicited by a gray market drug seller.

Keep an open dialogue on social media with other health care professionals and pharmaceutical industry representatives. Social media has shown to be a powerful means of advocacy. Take to Twitter, Facebook, and other platforms to raise awareness on issues causing drug shortages. Appeals directly to pharmaceutical industry companies and representatives may be effective to get the dialogue started on resolving quality issues.

Write or call legislative representatives to keep drug shortages on their radars. Keep your professional society engaged. Let your Congressional representatives know that drug shortages have real consequences for patients, and, although progress has been good, the level of shortages reached in 2011 should never happen again. Keep your professional society informed of how shortages continue to affect your practice, research, and patients.