Originally published in "Discussions with Don S. Dizon" on The Oncologist.

Originally published in "Discussions with Don S. Dizon" on The Oncologist.

By Don S. Dizon, MD, FACP, FASCO, and Joseph McCollom, DO

Twiend: Twitter + friend. It’s a term I coined a while ago to acknowledge people I’ve gotten to know, though we’ve never met IRL (in real life). In time, twiends become important to me, and simply seeing their posts show up on my Twitter feed can be enough to bring a smile to my face. Although much of Twitter is professional banter about shared interests or light-hearted conversation, you can really get to know someone, and when that happens, for lack of a better word, it’s enlightening. I always say social media is a nice way for others outside of medicine to see just how human clinicians are. But, more and more, I realize it’s a way for professionals to see the humanity in each other too.

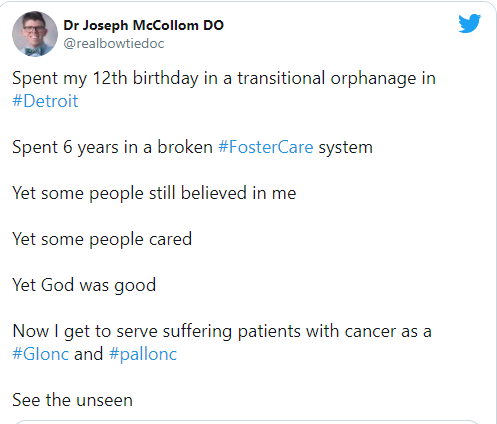

One such twiend is Dr. Joseph McCollom (@realbowtiedoc). Dr. McCollom is a subspecialized medical oncologist in the treatment gastrointestinal malignancies as well as an expert in supportive and palliative care for patients with cancer. He currently has a mixed clinical practice at a cancer institute in northeastern Indiana. We had exchanged several tweets about palliative care, bowties, and the TikToks I’ve been posting. In early February, Dr. McCollom posted a tweet that really stayed with me. In it he discussed his experience in foster care.

I was struck by how raw it was. In those very few lines, I felt his sense of being alone, of finding hope, and good people, and ultimately, becoming a physician. I decided to reach out to him, to get to know more about his life, and he graciously agreed to write this with me.

I wanted to know how he ended up in foster care, and what it was like for him, to enter it at the age of 12. He explained:

“I spent my 12th birthday in a transitional orphanage prior to entering the system. My parents divorced when I was in kindergarten and I lived with my mother. However, she suffered from severe bipolar disorder, and this kept her from holding a consistent job or being a consistent parental figure. As her disease worsened, she required inpatient psychiatric stays to stabilize her and I got shuffled into the homes of caring friends and distant family, but nothing was permanent. Eventually, Child Protective Services got involved and felt our living conditions were a danger to my health and growth, and that’s how I ended up in foster care. I still remember being so unsure of who I was and what I'd end up becoming.

“Our foster home held anywhere from 10 to 15 children at any given time. The oldest children in the house were 19 to 21 years old, aged out of the system but without the life skills to live in the real world. Unable to sustain themselves, these foster alumni fell back on the only support they'd ever had. The youngest in the house—ranging from infancy to 5 years—were often the children of foster alums. It was so easy to feel like a statistic—stuck in the system and doomed to repeat the cycle.”

As he told his story, it struck me how miraculous it was that he made it—that he was so resilient. To this, Dr. McCollom continued:

“I received a helpful grace in a way. There were individuals who recognized value in me and invested their time and energy, often with no professional or familial obligation to do so. They gave me the emotional, mental and spiritual foundation I needed to be protected and thrive. High school was extremely difficult. I had a great deal of low self-esteem and I contemplated suicide more often than I'd like to admit. I had very few close friends and mostly kept to myself.

“The friends I did have truly became family to me. I remember an academic honors night when everyone's parents were escorting them across the stage to receive their certificate of achievement. I had achieved academic success but was alone. My dear friend, eventually a groomsman in my wedding, received his own honor with his parents, then doubled back to me. He pranced on stage, grabbing the rose intended for the mother of the honored students and clutching it with his teeth.

“70% of foster care children dream of college, but only 3% graduate. Despite this, I found college transformative. I relied on my faith significantly. I had little, if any, financial or emotional support from either biological or former foster family. During college breaks I would work to clean the dorms to keep free housing. I would take summer classes as there was no home for me to truly go back to. My first summer of college is when I took lessons to learn how to drive for the first time, at 19 years old. I'd never been behind the wheel before and didn't even know the basics. I had the bravest instructor on the planet! I kept working through medical school, at one point holding three jobs simultaneously to attenuate the debt that was building up.”

As we discussed, I found myself riveted to his story. I knew he had married and wondered how he met his wife:

“A solid spiritual foundation and community really stabilized me, and many of my closest friends (including my wife) were those I met in this time. I was finally able to come into my self-identity for the first time. In college, I carved away a lot of the abuse, neglect and negative images that had built up over my childhood to reveal the person underneath who'd been there all along. By then, I was dating my wife and her parents and siblings were and remain the most outstanding surrogate family I could ask for.”

As he told his story, you could almost sense how he transformed. He then said something that was as poetic as it was true:

“Suffering without support creates hopelessness and despondency. Suffering with support creates resiliency and tenacity. We all are faced with challenges which test the limits of our physical and emotional endurance.”

We talked about challenges in medical school and how he settled on a career in oncology. He explained:

“As a medical student I listened to an oncologist, Dr Jason Beckrow, recall Randy Pausch's 'Last Lecture,' the Carnegie Mellon professor who talked about really achieving his childhood dreams. It was Randy's legacy lecture for his children as he'd been diagnosed with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Sensing the passion in Dr. Beckrow’s voice, I knew then I wanted to be an oncologist, and Dr. Beckrow became a personal friend and mentor. He embodied both palliative and medical oncology united in one individual, both in philosophy and board certifications.”

“To me, palliative and supportive oncology is key to being competent as a medical oncologist. It's an acknowledgement that cancer is a complex disease that impacts more than just physical wellness but permeates into a patient's personal identity, spiritual sense, and emotional stability. As cancer treatments continue to advance and survivorship becomes more attainable, the synergy with palliative and supportive care becomes more critical. I love that I get an opportunity to practice both clinically.”

Finally, I wondered if he ever looks back at the 12-year-old boy. If so, what does he say—and what would he say to those in the same situation? His answer:

“As an oncologist, whenever I deliver the news of an advanced malignancy or an unfortunate progression, I pause and recall that frightened boy without a family and without a future. It helps me empathize with the magnitude of their pain, and it keeps me grounded in a tempered but realistic hope.”

I love this. To me, most of oncology is about instilling such hope in people with cancer—those hearing it for the first time and those living with it as advanced or metastatic disease. It is something that, as oncologists, we should strive to maintain regardless of circumstance.

Recent posts