Many people believe the debatable position that academic centers provide better outcomes.1 Presumably, it’s partly due to having experts in academic centers not available in the community. However, academics are not rewarded for dissemination of quality improvements as much as publication. I will use an example from my hospital and suggest five ways to reward clinical researchers who communicate better how to implement their research findings, so we can improve cancer care in the community more easily.

Many people believe the debatable position that academic centers provide better outcomes.1 Presumably, it’s partly due to having experts in academic centers not available in the community. However, academics are not rewarded for dissemination of quality improvements as much as publication. I will use an example from my hospital and suggest five ways to reward clinical researchers who communicate better how to implement their research findings, so we can improve cancer care in the community more easily.

I work in Lowell, Massachusetts, once a leading industrial city that has struggled with the transition from manufacturing. Lowell has higher tobacco use and substance abuse rates than many other cities, as well as higher poverty levels and less social support for patients. Usually, head and neck cancer cases are pretty advanced. Many patients can’t travel to Boston, or don’t want to travel for seven weeks of daily treatment.

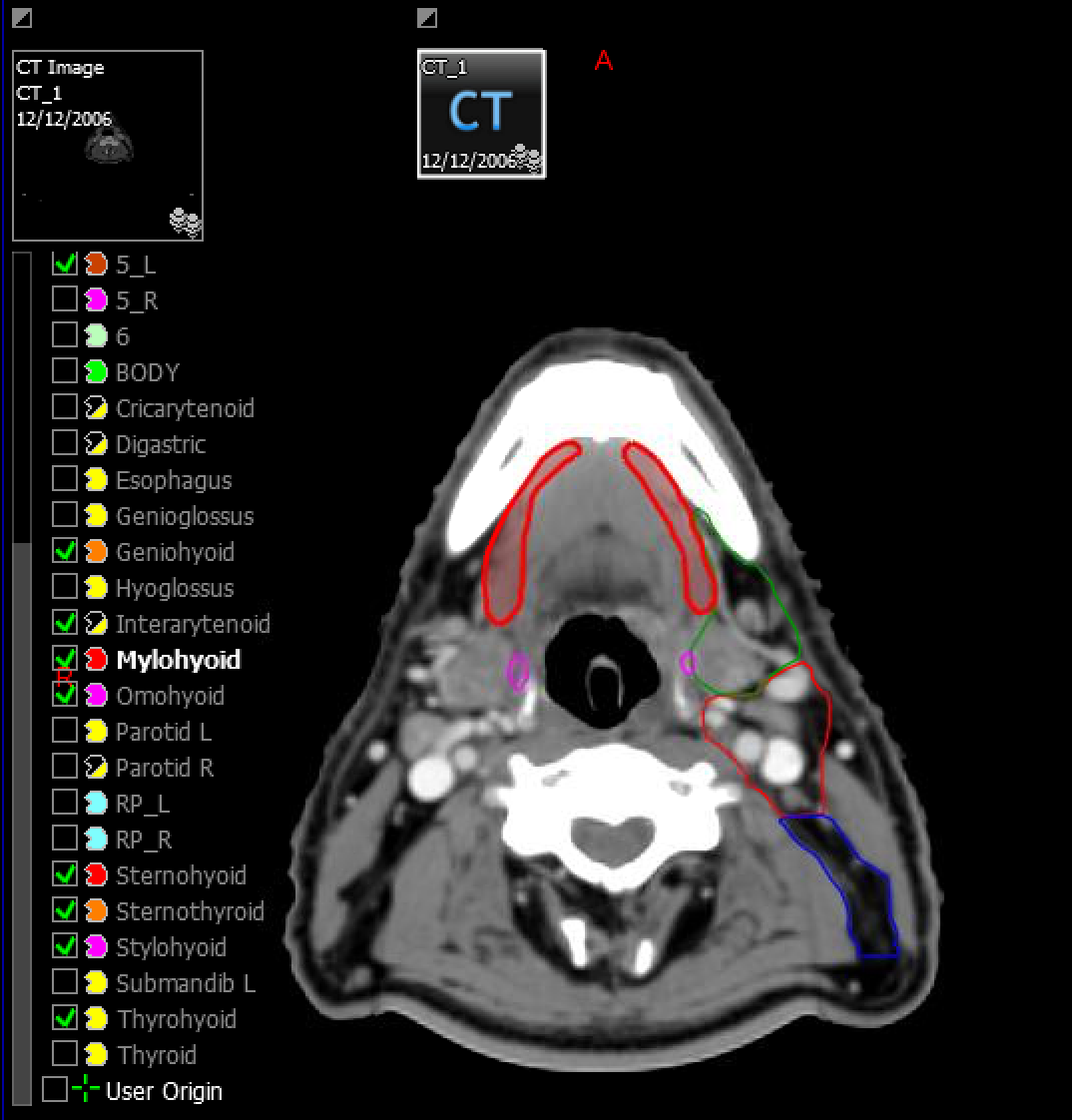

Head and neck cancer radiation is one of the more toxic treatments in radiation oncology, with cancer control that depends upon controlling the side effects of treatment and avoiding breaks. I’m always looking for clinical pearls to make treatment a little easier.

In Boston, I met a visiting researcher who had published on using gabapentin to lessen pain, opioid use, and the need for feeding tubes to cope with mucositis. The researcher was very engaging and enthusiastic about it, but suggested I read the research when I asked how they did it.

None of the researcher’s articles gave a dose schedule or plan on how to implement the drug. I sent email and left a message at the office; no reply. I contacted another lead author; no reply. I finally reached out to a friend in the department, connecting me to the researcher’s nurse for the information. After we vetted it with our pharmacist for an implementation plan, our quality improvement results have been remarkable so far:

|

Endpoint |

No Gabapentin |

Gabapentin |

|

Treatment Break |

7% |

0% |

|

G-Tube Use |

40% |

20% |

|

Opioids for Pain |

90% |

56% |

|

Median weight loss (lb.) |

8.5 |

4.5 |

Our baseline narcotic use isn’t too different than some published literature given our higher risk population.2,3 We did well with gastrostomy tube rates but it improved with pentoxifylline.4-6 It took only three or four meetings and some internal emails to implement. The key missing piece was translating the research into clinical practice. Getting practical guidance from the researcher’s nurse took over 2 years.

It should not be this hard.

Academic physicians often implement advances earlier because they innovate and treat larger volumes of patients with specific diseases. Head and neck cancer treatment is complex enough that expertise is linked to improved survival.7,8 More experience provides the opportunity to “fail faster” but that doesn’t make it into the publication.

It is no surprise translation from publication to implementation is lousy. Only 11% of randomized trials give enough detail to practically use in clinical practice.9 The higher the journal’s impact factor, the less likely the trials gave practical information for true clinical impact. Maybe more detail is discussed informally at academic meetings, but that’s not published so it doesn’t help me or other doctors treating over 70% of patients with cancer in community-based practices.

From my conversations with many academic colleagues, translating research to practice often falls through the cracks in terms of value for career promotion. It varies by hospital, but career advancement depends upon research grants, publications, teaching (students/trainees), and direct patient care. Increasingly in the U.S., the nonprofit academic centers seem to want mostly more patients seen and treated. With fewer grants to fund viable careers, academic clinicians have to see more patients. With the increasing amount of time spent on patient cancer and documentation, is it a surprise that academics may not have time or see value in communicating less formally?

Publishing isn’t enough—there is an ethical responsibility to disseminate improvements. But it needs to be practical as well for clinical researchers to do with the decreasing amount of time they have for scientific communications.

What if academic researchers were promoted based upon widespread implementation of research rather than publication? If academic promotions committees included evidence of improving community-based cancer outcomes as a path to promotion, that might make it time well spent for academics to communicate better outside the ivory tower.

Here are five ways we can use internet-based communication to make it easier for academic innovators to get credit for their work:

1. Build your own website. Make the clinical implementation protocol a draft for users to download. Make it an easy-to-use quality improvement project that may meet Maintenance of Certification requirements for your specialty so other docs want to try it. Ask for their emails to download so you have a database of people trialing your innovation. Follow up with them so you have testimonials to give to the academic promotions committee that show your innovations matter. Bonus: the website can highlight you and provide a way to improve your academic reputation separate from these projects. If you’ve spent months to years working on research, why not spend a little more time formatting your work for others, who can give you feedback to show your work matters?

2. Have your hospital/department set up the website/portal. Less labor intensive but then you don’t control it. If you have a great working relationship with your department chair, great. Otherwise, the institution may not highlight the hard work you did the way that you would. And you don’t keep it if you move to another institution.

3. Blog about it. Less formal than scientific communications, but it may be another way to interact with people and spread the word about your research. You can write it on your own blog or it’s easy to set up on LinkedIn, Medium, Tumblr, Blogger and others. LinkedIn has the advantage of sharing your expertise with your professional network. You can also write it up for your hospital; I’m sure they would love content to share on social media for you and have the platform to do it. I’d recommend posting somewhere you “own” it, then letting the hospital repost it.

4. Make a draft version trackable and downloadable. For a platform that is more focused on measuring interest than collecting detailed feedback, consider using Slideshare, now part of LinkedIn. You can upload a draft protocol to implement, share caveats, and get feedback. You can also show how many people have seen and downloaded your work. You may get comments but much less likely than options 1 or 2.

5. Share on social media. You can share easily on Twitter, Facebook, and elsewhere informally. However, this is likely the least time efficient way to do it. It doesn’t add value unless you are already interacting and using these communications platforms with the right people interested in your research. Not really much to measure or share with the promotions committee directly.

The only reason I could make implement this gabapentin protocol work was persistence. It took longer than it should because I’m a generalist running around treating everything.

If researchers make it easier for community docs to implement research that works, it may help academics both increase and demonstrate the value they add. I’m not in academics, but to save time for others I’m using options 4 & 5 to make a draft gabapentin protocol downloadable for others to implement. And if the authors of the studies want my feedback for their academic promotion review, please email me back and I’ll write a letter of support!

References

- Burke LG, Frakt AB, Khullar D, et al. Association between teaching status and mortality in US hospitals. JAMA. 2017;317:2105-13.

- Murphy BA, Beaumont JL, Isitt J, et al. Mucositis-related morbidity and resource utilization in head and neck cancer patients receiving radiation with or without chemotherapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:522-32.

- Allison RR, Ambrad AA, Arshoun Y, et al. Multi-institutional, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to assess the efficacy of a mucoadhesive hydrogel (MuGard) in mitigating oral mucositis symptoms in patients being treated with chemoradiation therapy for cancers for the head and neck. Cancer. 2014;120:1433-40.

- Vlacich G, Stavas MJ, Pendyala P, et al. A comparative analysis between sequential boost and integrated boost intensity-modulated radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy for locally-advanced head and neck cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2017;12:13.

- Lango MN, Galloway TJ, Mehra R, et al. Impact of baseline patient-reported dysphagia on acute gastrostomy placement in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma undergoing definitive radiation. Head Neck. 2016;38 Suppl 1:E1318-24.

- Bhavani MK, Hutcheson KA, Barringer DA, et al. Gastrostomy tube placement in patients with oropharyngeal carcinoma treated with radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy: factors affecting placement and dependence. Head Neck. 2013;35:1634-40.

- David JM, Ho AS, Luu M, et al. Treatment at high-volume facilities and academic centers is independently associated with improved survival in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2017;123:3933-42.

- Lassig AA, Joseph AM, Lindgren BR, et al. The effect of treating institution on outcomes in head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;147:1083-92.

- Duff JM, Leather H, Walden EO, et al. Adequacy of published oncology randomized controlled trials to provide therapeutic details needed for clinical application. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:702-5.

Recent posts